We do not usually associate the two; but, there it is: a Van Gogh hanging somewhere between one of the world's largest collections of antiquities and the Sistine Chapel.

We do not usually associate the two; but, there it is: a Van Gogh hanging somewhere between one of the world's largest collections of antiquities and the Sistine Chapel.

More than four million people visited the Vatican Museums last year. I was was one of them. For those who have not made their own pilgrimage, it is difficult to describe the vast, Byzantine compound that holds the Catholic Church's collections. With objects as diverse as Egyptian artefacts and Sevres porcelains, the "museum" is divided into several exhibitions, conjoined with palaces that make up the Pope's apartments. Together, they are nearly impossible to see it all in a single day or, even, week. And, if you are like me, mentally exhaustion sets in after an hour. So, it is understandable that most tourists make their way directly to the brightest stars in the collection (e.g. Raphael's frescoes, Laocoön), without seeing what in other museums would be show stoppers.

The Vatican has a sizable collection of modern and contemporary religious art. These works range from mid-nineteenth-century artists to today and are hung in a series of dimly-lit, basement rooms leading to the Pope's apartments. Visitors are given the choice of a short cut directly to the Sistine Chapel or a fifteen-minute walk through the rooms where the Modern Collection hangs, sometimes unlabeled. Most choose the direct route. Even those who take the long way end up rushing past works by Auguste Rodin, Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, Giacomo Balla, Otto Dix and many, many others.

It was there I saw Pietà by Vincent Van Gogh. I cannot stop thinking about it. This post is an attempt to figure out why.

I am not nor have I ever been obsessed with Van Gogh. Of course, like many, I feel admiration for his singular way of seeing the world. I feel a shock every time I see one of his works in person. His sculptural use of oil paint and familiar colors combined with acrobatic compositions, makes common places, people and things members of alternate realities. His debilitating solitude, tortured genius and early death make him a rock star of art. (Back in the 90s, two posters, one of Kurt Cobain and the other of Van Gogh, hung above my roomate's desk.)

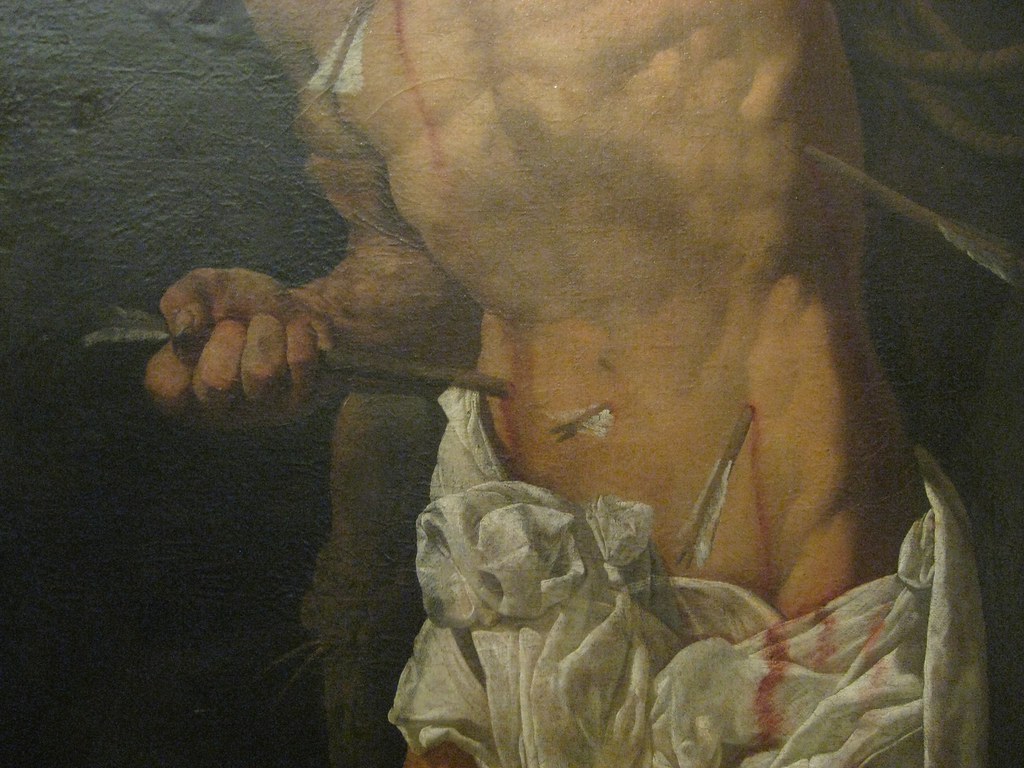

Some scholars believe that Van Gogh's Pietà, showing the dead, tortured body of Christ after the Crucifixion, is actually a self-portrait. (Note the red beard.) While in the Hospital of Saint-Rémy, housed in an old monastery,Van Gogh wrote his brother Theo: "I am not indifferent, and pious thoughts often console me in my suffering.” In any case, religious works by Van Gogh are rare. The Pietà is one of two biblical paintings he copied from Delacroix.

Van Gogh hugely admired Delacroix, mentioning him more than 95 times in personal letters. In particular, he admired Delacroix's use of bold and vibrant color.

Writing to his brother about Delacroix's Pietà, which he had in the form of a lithograph, Van Gogh wrote:

The Delacroix lithograph La Pietà, as well as several others, fell into my oils and paints and was damaged. This upset me terribly, and I am now busy making a painting of it, as you will see.

We do not know if he was referring the painting in the Vatican or the other version, hanging in Van Gogh Museum, which some believe to be made late. The Vatican Museum of Modern Art did not purchase its painting. Like many other works, Pietà was a gift from a member of the Church, who donated it his diocese in New York sometime mid-century. Of the two versions, the Vatican's is much smaller. It is also darker, which is, perhaps, more a result of not being as well cleaned. But, the darker hues, combined with the dim lighting, in my opinion, imbue the work with greater pathos.

We should all be aware by now that most paintings we see in museums were never meant to be hung in a public space, let alone under modern, high-voltage lighting. While I do not know the original context for the work–if there even was a context–the overlooked space on the way to the Sistine Chapel seems a fitting.

Does Baroque art burn more calories than other genres? What did that couple in leather pants say about Mary Magdalene looking hot? Was Luca Giordan0 the first street artist? Is linseed oil more environmentally friendly than egg tempura?

Does Baroque art burn more calories than other genres? What did that couple in leather pants say about Mary Magdalene looking hot? Was Luca Giordan0 the first street artist? Is linseed oil more environmentally friendly than egg tempura?

The

The