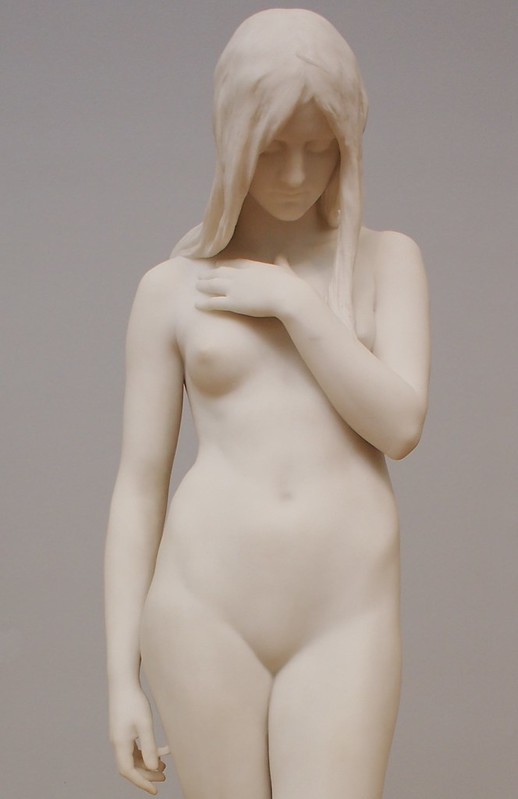

Yesterday, Waldemar Januszcak, art critic for The Sunday Times, wrote a scathing review of “A Victorian Obsession,” an exhibition of 52 paintings by Frederick Leighton, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, and Albert Moore, among others, on show at the Leighton House Museum. Subtitling his review “Droopy damsels in distress take center stage . . .” Mr. Januszczak belittles and dismisses the works as “nonsense,” “divorced from reality,” and “grotesque.” This is not the first time Mr. Januszcak has written dismissively about nineteenth-century academic art and artists. (He wrote similarly negative reviews of recent exhibitions on John William Waterhouse.) And, this isn’t an angry response to his article, where I feign injury on behalf of a genre of art I happen to like. Rather, I feel that Mr. Januszczak repeated a standard approach to Victorian art — one that constantly sees it only in opposition to Impressionism and Modernism — that needs to be retired, because it misses the point. Whether or not we like them, these works say a great deal about the culture that produced them.

The occasion of Januszcak’s article is a loan of 52 works owned by Juan Antonio Pérez Simón, a Spanish Civil War émigre raised in Mexico, to the Leighton House Museum. Mr. Pérez has been collecting the works over the past twenty years; a period accompanied by increased values for the works at auctions, scholarly publications, and museum exhibitions. Long held in private collections, many works from Pérez’s collection have not been seen in public, let alone as a group. This collection does not represent the bulk or, arguably, the best of these artists' oeuvres. Many more can be found at the Victoria & Albert Museum, Tate Britain, and the Bristol Museum of Art.

Reading Januszcak’s review, my first instinct was knee-jerkingly defensive. He talks about the absurdity of the subject matter. He draws a comparison between the brief, meteoric success of Leighton and Alma-Tadema and the seemingly unsustainable trends in contemporary art.

If I were a nouveau riche Russian with a Kensington house full of stuff brought at Frieze, I would instruct my chauffeur to take me immediately to Christie’s, where I would start selling as if there were no tomorrow.

(One almost wonders if Mr. Januszcak just finished watching Bertold Bretcht’s “Seven Deadly Sins of the Petite Bourgeoisie,” and it spilled over to the review.)

Apologists often defend Leighton and Alma-Tadema on technical grounds: “Can’t you see these artists were educated, thoughtful . . . a true craftsman!?” But, that isn’t a winning argument. After all, Waldemar Januszczak understands quality. He has done several, thoughtful series on Old Masters. But, like many critics, he has an inherent disdain for the artistic period between the late-eighteenth-century and avant-garde movements of the last half of the nineteenth century. He writes:

. . . Leighton was just a year older than Manet. But while Manet was ushering in the impressionist revolution, in 1871 Leighton was imagining four Greek nymphs on a beach gathering pebbles in their floatiest robes.”

He makes Leighton sound convincingly backward. But, there is another point of view.

Having spent the past decade researching mid-nineteenth-century works of art, artists, and arts education, I am clearly biased. (I have also felt isolated and frustrated by my art-historical colleagues who would gladly write another book on Picasso’s treatment of cuticles.) But, I also feel that summarily ridiculing these works from our present point of view (e.g. comparing Leighton to Manet) misses an opportunity to discuss context in which the works were made. You don’t have to like these works. However, you should realize they are magnificent commentaries — often unintentional — on the aspirations of of the British Empire at its height. The art, with all its classical imagery and idealistic affectations, is a manifestation of the ideals of those industrialists in Bristol, Liverpool, and London who saw their generation as the latest claimant to the glories of the Roman Empire.

.png)

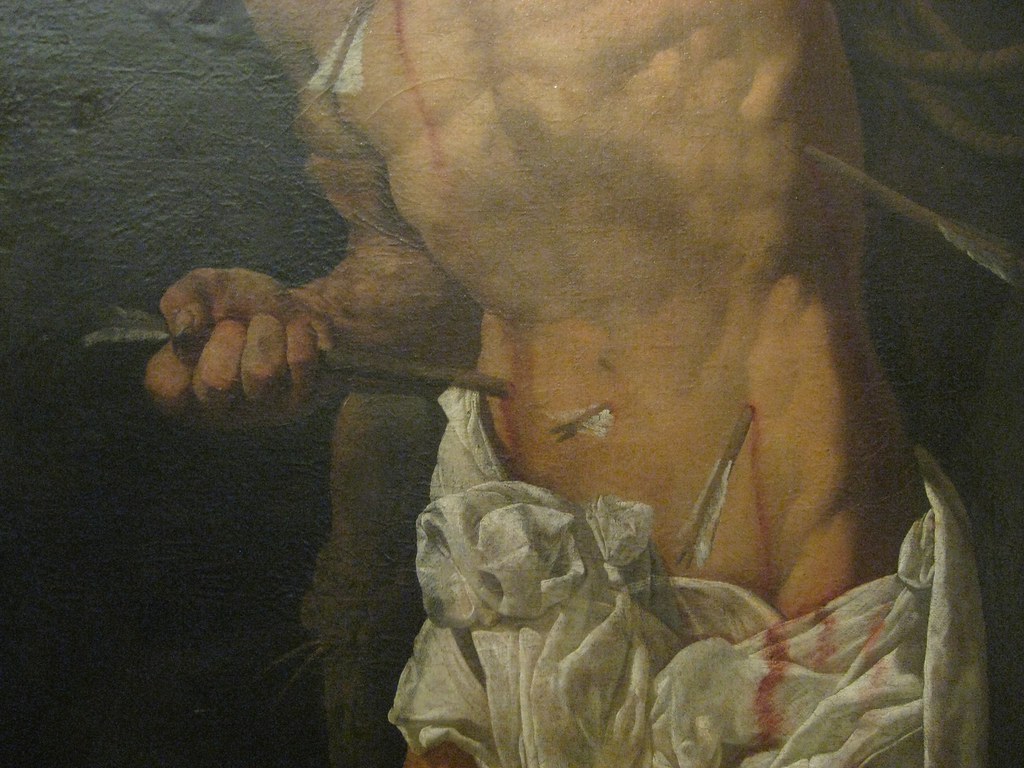

Januszczak rightly points out the ridiculousness of Alma-Tadema’s work The Roses of Heliogabalus (1888), which imagines the moment the obscure Roman ruler showered and suffocated a crowd with flower petals. Alma-Tadema, Leighton and Moore are often referred to as Olympian painters, for conjuring these kinds of scenes, where attractive British women and men are dressed in vaguely classical costumes, and placed in meticulously-created and improbably grandiose settings. They are meant to be unrealistic. They are physical manifestations of the aspirations held by a generation of Belle-Époque Brits. It’s also one held by many — wealthy or not — today. Weren’t many of these nouveau riche and landed gentry funded by siphoning off colonial resources? The ridiculousness of the Alma-Tadema's work does not come from the quality or subject of the painting. It is from the lack of embarrassment of riches by those audiences that related to it. (Is the fat old man in the background a Victorian banker? Is that the 99% drowning in mortgage debt?) I don't know if Alma-Tadema intended it as social commentary. Whether or not he appealed to the elite by illustrating their fantasies or subtly criticized them, it is still a commentary on the times.

For me, Olympian works of art are less comparable to those showing at the Frieze Art Fair than to Apple products. Januszczak rightly points out that original oil paintings were purchased by contemporary industrialists for enormous sums. But, he fails to say that artists like Leighton made most of their money in the reproductions of their works — prints in popular journals that were torn out, framed, and hung in many households. This blows a hole in the theory that these artists were painting solely for the monied, elitist few. Like having the latest iPhone, a Leighton print hanging on your wall probably did little to actually increase quality of life or help humanity. But, it was what marketers today would call an "aspirational lifestyle purchase." These works are a remarkable insight to the British Empire and its people — at least those in the UK. Bringing up Manet and the avant garde brings us back to a conversation that has been played out ( I can see Roger Fry's angry ghost saying: "These artists were out of touch with Modernity!") Manet had nothing to do with it. Januszczak wants to fold this work into a standard narrative from the playbook of art historians and critics without really thinking about what made these works truly popular.

I also agree with Januszczak that the great interest some people have in these paintings is puzzling. Akin to Januszczak’s quick dismissal, they love these paintings without considering them. The fact that they are becoming popular again — even inspiring custom luxury room scents (More here) as Januszczak points out — is another opportunity to examine what these Olympian painters distilled in their own era, in the desires of a Spanish billionaire, and the many people who see this art today and love it.

The

The