Have you ever had the experience seeing a remarkable work of art and after reading the name of the artist, wondering "Why haven't I ever heard of her before?!" This happens to me all the time. As I travel around the world to major and provincial museums, attend auctions, and visit private collections, I see astounding masterpieces by artists whose anonymity defies the quality of their work. I write down their names and do my best to find out who they are. Often I learn that these sculptors and painters are well known to seemingly everyone but me. But, in some cases, I find that there is little known about them. I call these artists "Forgotten Masters." And I have a list of more than 300 so far.

These artists range from the fourteenth century to the present. Some are the equivalent of one-hit wonders — making an award-winning work and never quite reaching that level again. But many were consistently skilled and hugely influential. They have been left out of the standard narrative of the history of art through various circumstances (e.g. dying young, working in provinces, becoming teachers, being out of step with the zeitgeist, or being women).

Last year, I gave a lecture series on the development and careers of several well-established Old Masters. The lectures were attended in person by professional artists, who added their remarkable perspectives to my art-historical approach. We recorded several of these and put them online. (You can access them here.) Some of these online recordings were visited more than 150,000 times.

This Fall, when our lecture series begins again, rather than revisit the careers of well-researched artists whose works have been examined and broadcast many times — and for good reason — my plan is to bring much needed attention to these Forgotten Masters. Because these artists are, by definition, difficult to find in museums, online, or libraries, I would like to create a collaboration between me, those who are attending the lectures, and anyone who wishes to participate online.

I WANT YOUR LIST TOO

I have narrowed my list of 300+ to about 50 names. But I know that my list is probably woefully incomplete. If you have thoughts on how it can improve, Please:

- Look through the list

- Tell me who I have missed. (Put their names in the comments or send me an email.)

- Berate me if I have included anyone unworthy of the list.

- Share the list with others who you think will be interested.

THE BEGINNING OF A CONVERSATION

Once we have a good amount of feedback and a solid list, I will start working on the lectures. Each lecture will discuss a Forgotten Master, his or her training, major works, influence, and place within the well-remembered artists of the time. Each lecture will be recorded, put online and accompanied by a post on BeardedRoman.com. These posts will be a major resource, where those who have additional information relating to the artist can share their findings.

SOME BACKGROUND

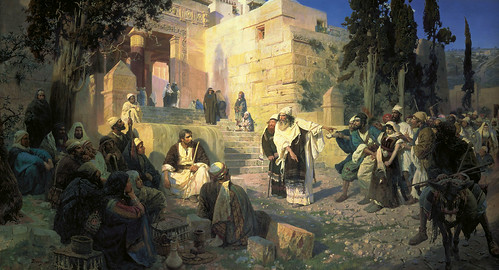

About ten years ago, I posted a few Forgotten-Master-themed posts on Bearded Roman. (You can see them here). By far, they have been the most visited posts on this site and are still the top links for Google searches for each of those artists. In particular, the post about Hugues Merles (French, 1823-1881) led to lively discussions online and off, and to one exhibition.

Over time, I hope that the artists we select together will be better known and that we can provide a resource for future studies.

DISCLAIMER

You may recognize some of the names on this list. Some of them may be well known to you or the larger world for a single work of art; but, unknown for the rest of their oeuvre or other contributions.

My criteria for being "forgotten" is no major catalogue or exhibition in the last 50 years OR not being discussed outside a small region (i.e. many artists are well known within their small community; but, little or no information appears outside of their native language).

My criteria for being a "master" is less scientific. It depends on whether or not their work is exceptional compared to their peers (e.g. fellow artists, collectors, critics) and whether or not their work had a lasting influence on others.

THE LIST

Click on the green dot next to each artist's name for my one-sentence description of the artist and a link to a representative work of art.

[gdoc key="https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1T4DqeejQeyAKgAvpvQRhbNO3NyqDthAI2r74rbWPNu4/edit?usp=sharing"]