With art historians earnestly looking for prominent female artists, it is surprising that so little is written about Fanny Fleury (French, 1848-1920). With the exception of Rosa Bonheur (French, 1822-1899), Fleury was perhaps the most successful female exhibitor in the history of the Paris Salon, having works accepted consistently from 1869 to 1882, and in many afterwards. She also exhibited at the Salons of Saint-Etienne and Dijon, and received an honorable mention at the Exposition Universelle of 1889.

With art historians earnestly looking for prominent female artists, it is surprising that so little is written about Fanny Fleury (French, 1848-1920). With the exception of Rosa Bonheur (French, 1822-1899), Fleury was perhaps the most successful female exhibitor in the history of the Paris Salon, having works accepted consistently from 1869 to 1882, and in many afterwards. She also exhibited at the Salons of Saint-Etienne and Dijon, and received an honorable mention at the Exposition Universelle of 1889.

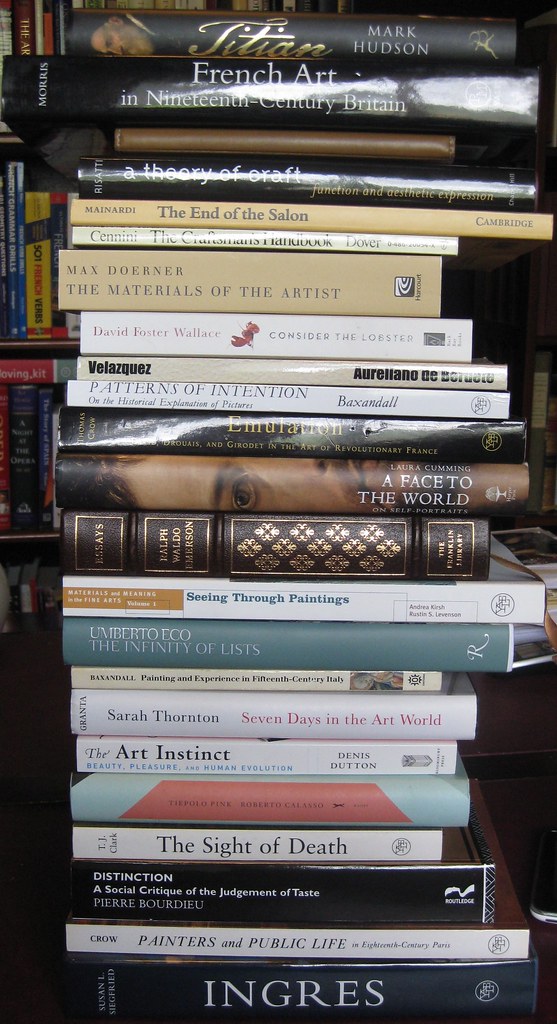

Fleury's academic credentials are impeccable. She studied with Jean-Jacques Henner (French, 1829-1905) and was later accepted to the École des Beaux-Arts as a student of Carolus-Duran (French, 1837-1917), where she was a classmate of John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925). (Speaking of her work at the 1884 Salon, one critic said Fleury had "equalled her masters," Henner and Duran.) Highly regarded by her peers, Fluery was elected an Officer of the Academie and an associate of the Société des artistes français.

Yet, for all her accomplishments in well-documented institutions and events, there is surprisingly little information currently available about the life and work of Fleury. (This is another instance where I am writing about an artists in hopes that it encourages others to contact me with additional information.)

Fleury was born outside Paris in either 1843 or 1848–most sources agree on the latter. It is possible–I stress "possible" for lack of form documentation, yet a great deal of circumstancial evidence–she is the daughter of Joseph Nicolas Robert-Fleury (French, 1797-1890), a successful history painter and on-time director of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and Rome; and, his son, the painter Tony Robert-Fleury (French, 1837-1912), who was also successful painter and who replaced Bougeureau as the Director of the Société des artistes français (If anyone can shed additional light, it would be greatly appreciated.) When she married, Fanny Fluery became Fanny Laurent Fleury; but, never included "Laurent" in her signature. So, whether or not there is an actual genetic connection between the three Fluerys, they must have come into contact with one another through the Acadamie.

It has been difficult to piece together a continuum of Fleury's production with the few works and accounts left to us. It appears that for a time–presumably early in her career–she created a number of still lives.

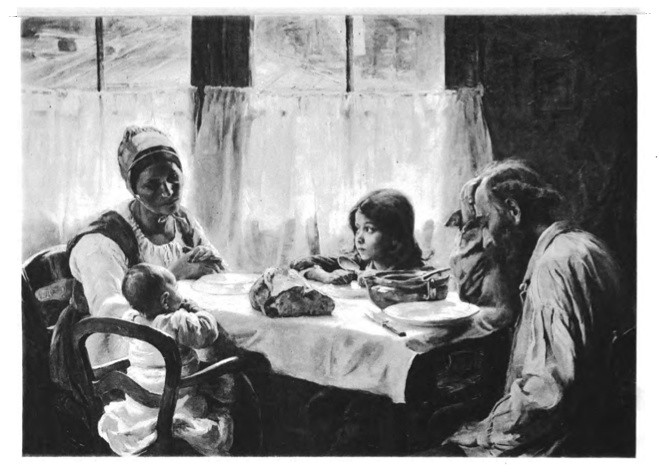

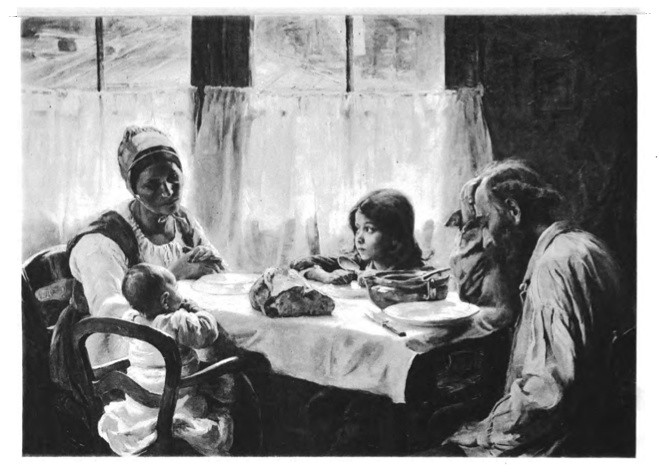

Under Carolus-Duran, Fleury distinguished herself as a portraitist. Her large-scale work Bebe dort (1884) exhibited in the Salon of 1884 along with Madame X by her classmate John Singer Sargent. Both pieces belie the the influence Corolus-Duran, who often combined monumental human figures in contemporary settings.

In Bebe dort (1884), a mother–perhaps a self-portrait of the artist–cradles her child, sitting together next to a cradle. Behind the figures, on the wall Fluery places a print of a business being ransacked by a mob. No one would imagine that scene actually being hung in a child's room. It is a clever use of a picture-within-a-picture, used often by Netherlandish painters in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, to create greater or multiple meanings within a work. The juxtaposition of the two scenes contrasts security and comfort of home with a threatening world.

At some point, Fleury set aside society portraits and dedicated herself to Breton scenes. In 1892, The American Magazine wrote:

Realism has likewise tempted another artists of great talent, Mme. Fanny Fleury. It is to the desolate lands of Lower Brittany that Mmde. Fleury goes for her subjects. She has painted som admirable marine scenes, but excels in depicting types of peasantry . . . every summer she goes to the seacoast, and in some retired cornes, unfrequentd by the tourist, prepares her picture for the next Salon. (The American Magazine, Vol. 34. New York: Frank Leslie Publishing House, 1892; p, 430.)

The quality of her work combined with her credentials certainly raise questions about the current dearth of readily-available information on Fleury's life and the location of her works. All signs point to a productive career. From contemporary records, we know that her works were regularly purchased from Salon galleries, and that her works were found in various French and American museum collections–none of which currently list those works in their public inventories.

Whatever the reason for Fanny Fleury's undeserved, forgotten status, she will only gain prominence as her works are rediscovered.

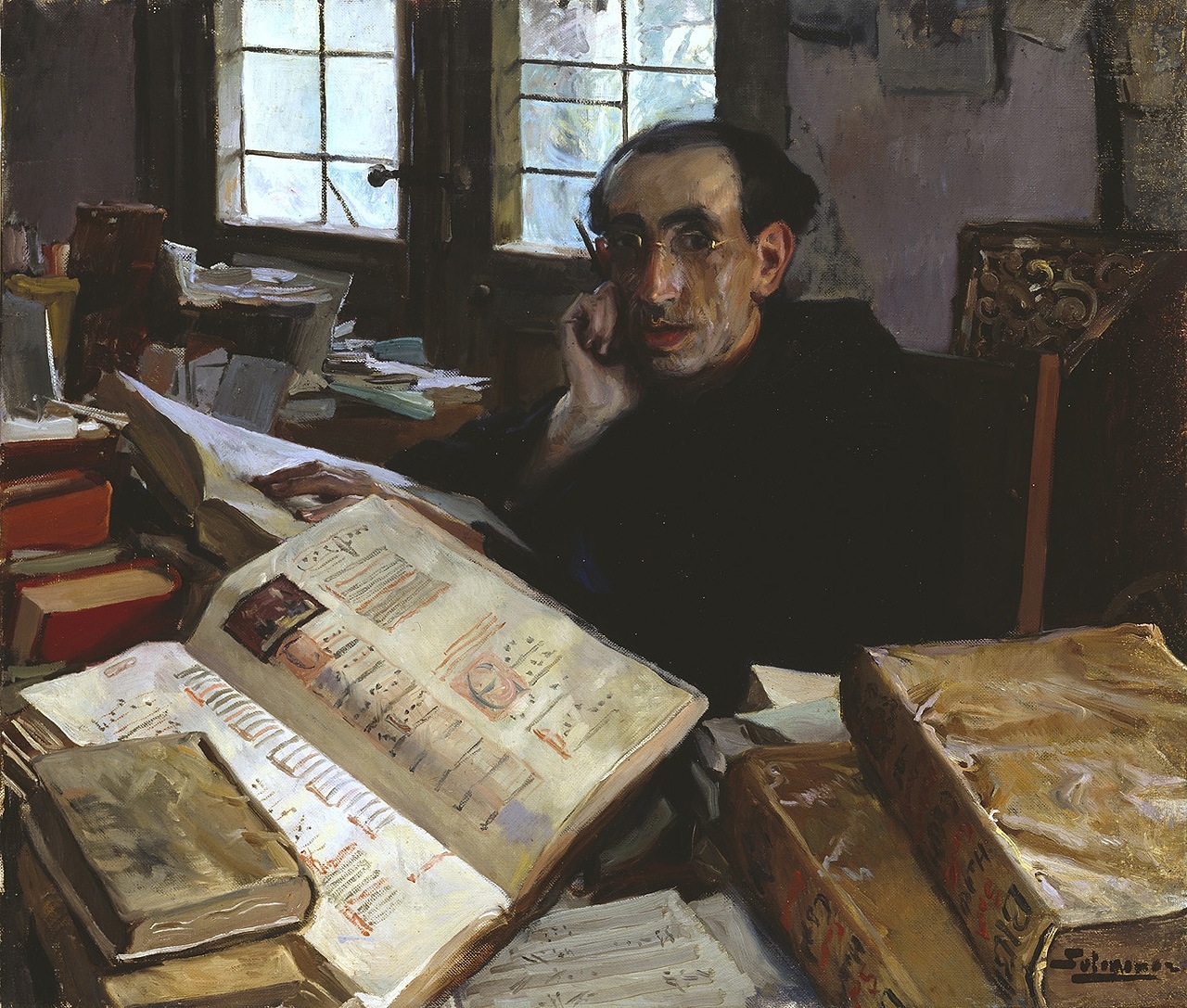

Guido Reni (Italian, 1575-1642) is one of the more important figures in the Pantheon of art history. He was born shortly after the Council of Trent, where the Catholic Church proposed sweeping changes to the arts in an attempt combat rising Protestantism. Reni became a leading proponent of a new aesthetic that clearly told stories through the use of large-scale religious and historical figures.

Guido Reni (Italian, 1575-1642) is one of the more important figures in the Pantheon of art history. He was born shortly after the Council of Trent, where the Catholic Church proposed sweeping changes to the arts in an attempt combat rising Protestantism. Reni became a leading proponent of a new aesthetic that clearly told stories through the use of large-scale religious and historical figures.