I'm in London just in time to see changes made to Tate Britain, and share a few snapshots from my visit.

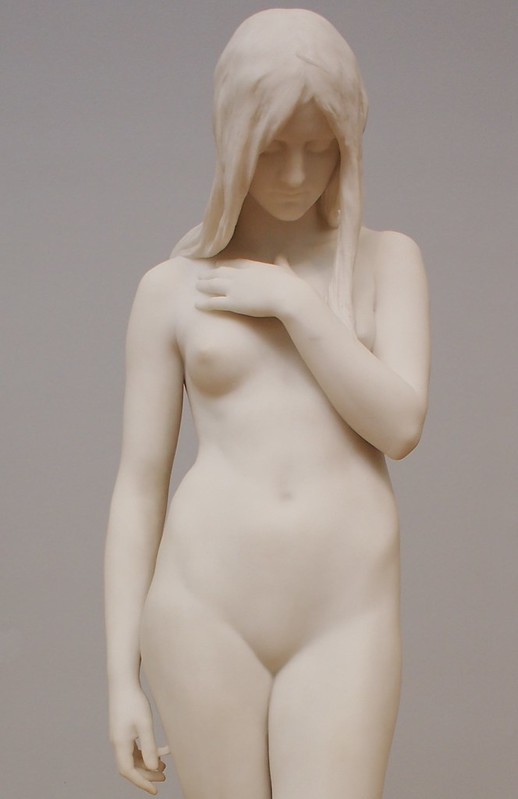

The Museum's collections have been rearranged and expanded. (Learn more here.) Works, such as Eve (1900) by Thomas Brock (1847-1922), have been taken from other museums — Eve was formerkly in the sculpture gallery at the Victoria & Albert Museum, where it stood on a very high pedestal — and put within the context of contemporaneous works.

With all works in chronological order, the Museum a visual feast of 500 years of British art. However, about seventy percent of eye-level wall space is given to art created in the last ninety years. One has to wonder why one of the museum's most popular paintings, The Lady of Shallot by J.W. Waterhouse is hanging some ten feet above a row of paintings, while cavernous space is given to "sound art" and "visual projections."

There, I've shared my nineteenth-century, figurative-art bias.

Now I can say without reservation that the Tate Britain is better than ever. Go see the paintings . . . and the sculptures!! Oh, the sculptures! They are worth visiting a thousand times.