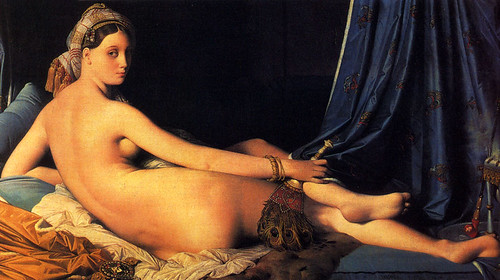

Three quarters of what constitutes painting is comprised of drawing. If I had to put a sign above my door I would write: 'School of Drawing,†and I'm sure that I would produce Painters.

-Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Studies for "The Grand Odalisque," 1814. Graphite on three sheets of paper, 10 BY 10 1/4IN. (25.4 BY 26.5CM.). Département des Arts Graphiques, Musée du Louvre, Paris.

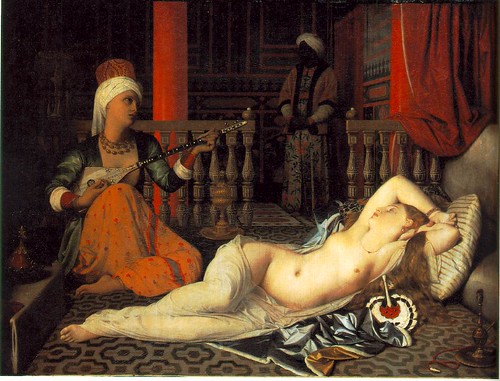

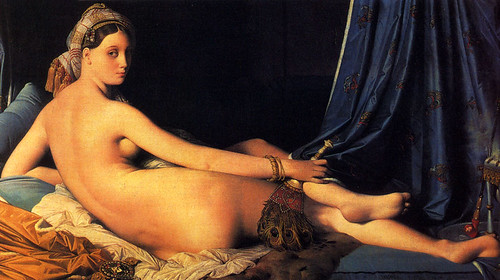

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, The Grand Odalisque, 1814. Oil on canvas, 35 1/4 BY 63 3/4IN. (89.66 BY 162CM.) Private collection.

Drawing was the fundamental teaching of the French art education system, a model that spread to the rest of the world.

In its original, seventeenth-century coursework, students submitted to a daily regimen beginning with copying modeles de dessin, plaster casts, and individual body parts. After years of practicing from inanimate objects, talented students were allowed to draw directly from nude models and compete for government commissions for work on the merit of their drawings.

Drawings Produced from 1800 to 1850

In the process of their study and work, nineteenth-century artists created specific kinds of drawings with distinct purposes. Because there was no widely recognized market, drawings were not made for the purpose of sale. Instead, the public purchased paintings or prints. However, this did not mean that the drawings were considered to be valueless. In the tradition going back centuries, David and Ingres kept stored and labeled drawings, and sometimes used them for instructional purpose.

Most of the drawings included in this post are by the prime example of academic drawing of the period: Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780-1867). Ingres was the undisputed leader of the École des Beaux-Arts after the death of David. Ingres was David’s star pupil and had been awarded the Prix de Rome from the French Government, allowing him to study directly from classical works in Rome. He returned to Paris in 1841 and dominated teaching at the École.

EDUCATIONAL DRAWINGS

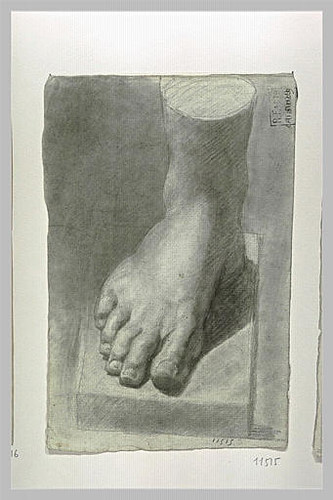

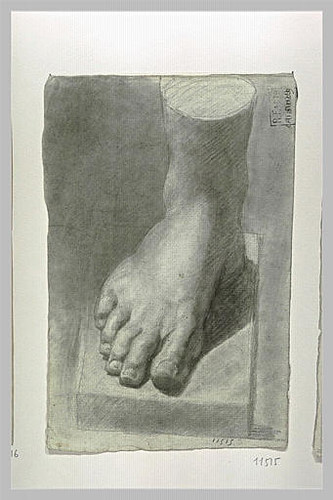

Individual parts of the body, from the plaster cast

Anonymous study of plaster foot. Musée d'Orsay. Paris, France.

Before students were allowed to work on the human figure, each was required to produce convincing two-dimensional reproductions of plaster casts made from ancient statuary. Greek and Roman works were considered representations of ideal beauty, and were often created using complex mathematical equations in pursuit of the Golden Mean.

The intent of this approach was to firmly establish a foundational concept of the human body in each student’s practice before he or she encountered wide-ranging variation in the natural human figure.

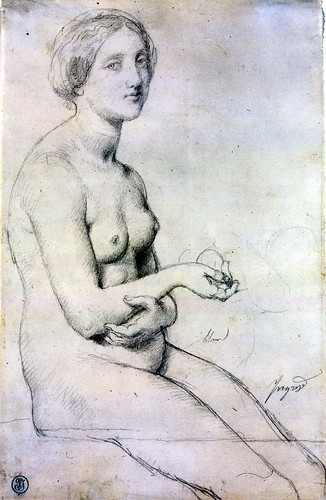

From the Nude

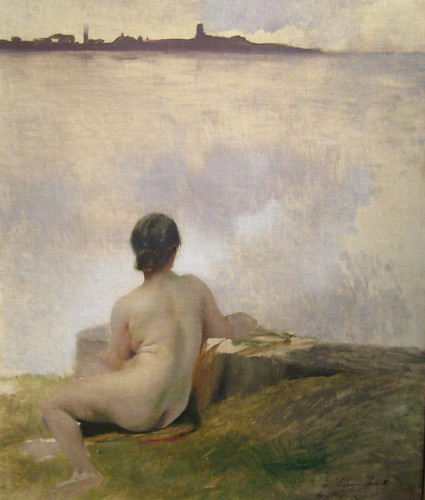

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. Study of Seated Female Nude. c. 1830. Musée Ingres.

From the early Renaissance to the mid-nineteenth century, mastering the human body was considered the supreme challenge and goal of academic painters.

This foundation was especially necessary for commercial success in France, where the most lucrative commissions came in the form of patriotic history paintings comparing the new French Republic to classical democracies in Greece and Rome.

The live drawing sessions were overseen by the head teacher of the École. In the beginning of the century, David arranged the school’s schedule around live model drawing.

The art critic Etienne-Jean Delécluze described the approach of Jacques-Louis David, who is responsible for the trajectory of the École in the first half of the century:

“in the eaves . . . facing the Pont des Arts . . . the model was posed twice a week, or rather every ten days, at the time. For the first six days the model was posed nude; the last three days, a model for the head only, and the studio was closed on the tenth day.â€

These drawings did not relate to any particular painting, but were understood to assist the painter in his mastery of the human figure.

Years after receiving his first lessons in drawing the nude from David, Ingres was one of the most prominent portrait painters in Europe. In a surviving drawing, we can see that even when working with a fully-clothed sitter, Ingres used his understanding of human anatomy to understand the structure of the body beneath the clothing.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Study for the “Portrait of the Baronne James de Rothschild,†c. 1848. Graphite on paper, 8 BY 5 1/8IN. (20.4 BY 13CM.). Musée Bonnat, Bayonne.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Portrait of the Baronne James de Rothschild, 1848. Oil on canvas, 55 3/4 BY 40IN. (141.8 BY 101.5CM.). Private collection

I'm fairly confident that Ingres died not tell the Baronne that he was imagining her in the nude.

PREPARATORY DRAWINGS FOR PAINTINGS

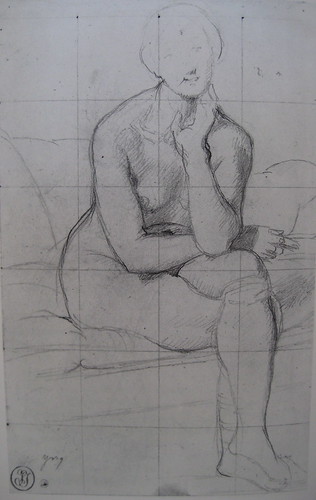

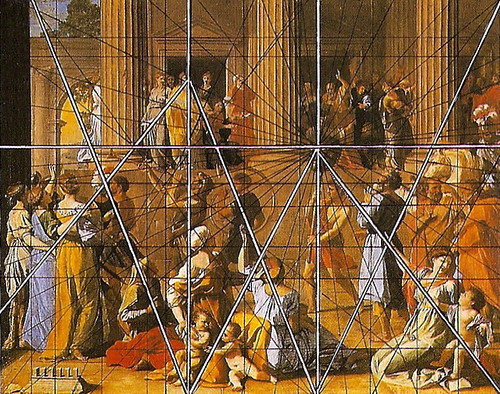

There were, broadly speaking, three classes of drawings created by artists trained in the École in the process of making a painting: the première pensée, the esquisse peinte, and the croquis. Again, Ingres will be used as the example.

The première pensée

Drawings were seen as the beginning of the painting process. An artist’s first idea, or première pensée, would be captured in a rough sketch with the intent of developing composition. Successive drawings would develop the idea found in the original and create a clearer or more thoughtful expression of what had only originally been sketched. Detail such as figures, stance and gestures come into focus.

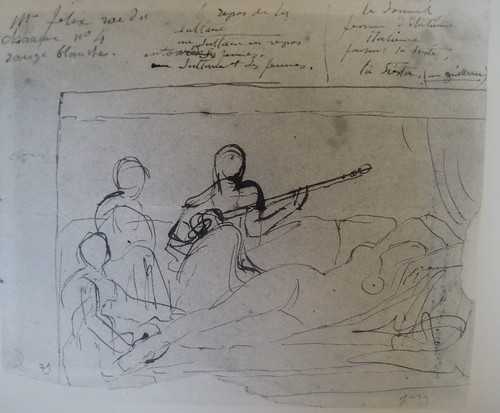

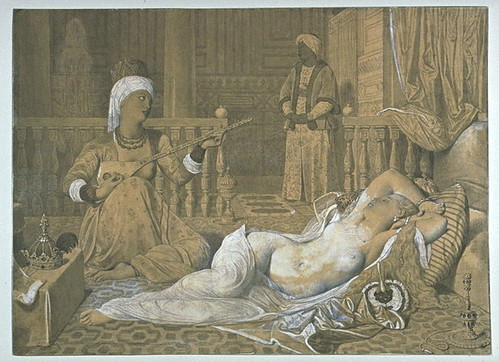

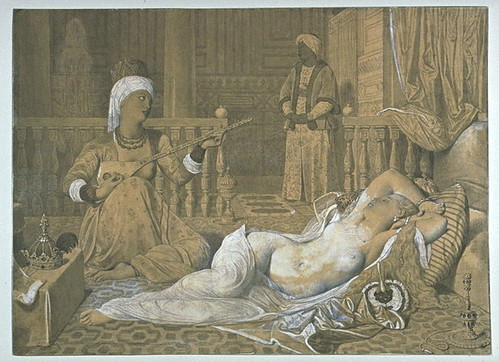

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Study for "The Odalisque with a Slave," 1839. Pen and ink on paper, 6 1/4 by 7 1/4IN. (16 BY 18.5CM.). Musée Ingres, Montauban, France.

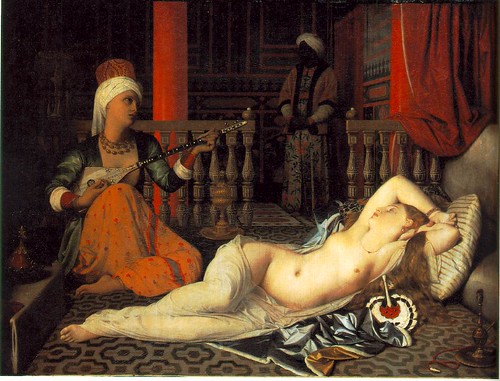

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, The Odalisque with a Slave. 1839.

This drawing by Ingres is the first known draft for his painting Odalisque with a Slave (1839). It is a very small drawing. The quick lines and lack of any detail are used as a starting point for further drawings.

The esquisse peinte

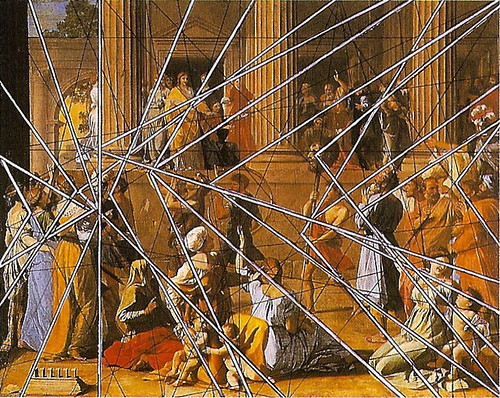

The second stage of drawing used by Ingres is referred to as the esquisse peinte and is used as a complete road map for the final painting. Much larger than the première pensée, it was often drawn to the scale of the final painting directly onto the canvas and then painted over by the artist.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Study for "The Odalisque with a Slave," 1839. Pen and ink, white pastel, and gouache on paper, 6 1/4 by 7 1/4IN. (34.5 BY 47.5CM.). Louvre. Paris, France.

The croquis

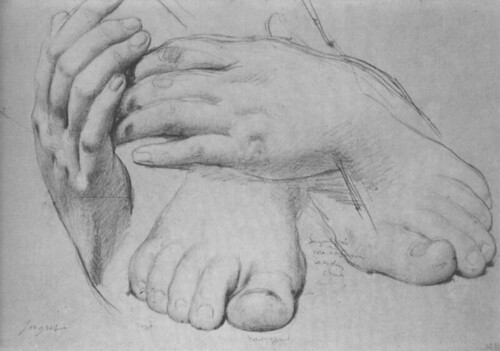

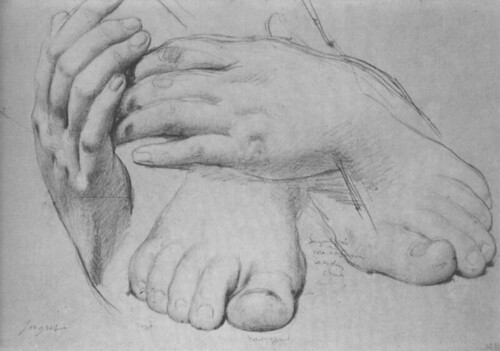

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Study of Hands and Feet for "The Golden Age," (1862), graphite on paper. Louvre, Paris, France.

Throughout the drafting process, areas of the painting that pose particularly difficult challenges (e.g. hands, feet, linen folds, facial expressions) are drawn sometimes multiple times and in multiple positions. In this way the adage of “measure twice, cut once†was applied to painting. In this way the artist could test multiple approaches to individual areas of the painting without jeopardizing the entire work.

This isn't your grandparents' classical music . . . wait, it is. But, now it is accessible in a highly visually and professional format:

This isn't your grandparents' classical music . . . wait, it is. But, now it is accessible in a highly visually and professional format: