Neuroesthetics: The Science of Art and the Brain

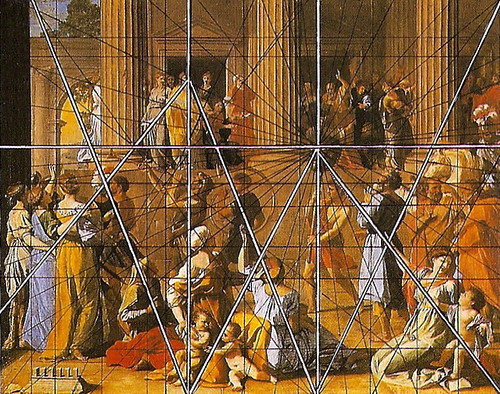

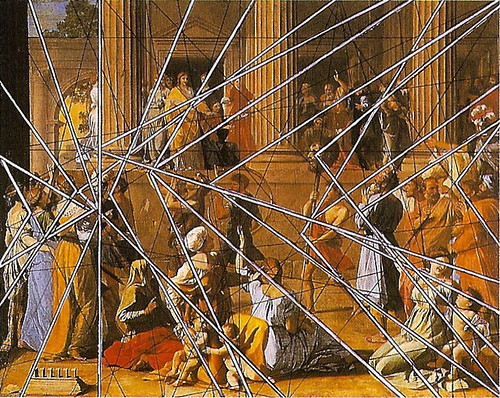

Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665) The Triumph of David. Oil on canvas. 118.4 BY 148.3CM. Dulwich Gallery, Dulwich, UK. Poussin is remembered for his highly structured paintings that influenced generations of artists looking for a more scientific approach to their painting. Three geometric analysis of this work are included in this article.

Over the past decade a new field of neurology has emerged, Neuroesthetics, with the intent of mapping the brain's reaction to the fine arts.

The term "neuroesthetics" and the field was pioneered by Dr. Semir Zeki, who is the first Professor of Neuroesthetics at University College London, founder of the Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neuroscience at University College London and the Minerva Foundation at UC Berkley, where he is an adjunct professor. The website of the Institute defines its work as seeking "to establish the biological and neurobiological foundations of aesthetic experience."

The notion of scientifically quantifying art might seem opposed a central purpose of art, which is subject to individual experience with an original work of art. In his long essay, What is Art?, Leo Tolstoy said it another way:

The activity of art is based on the fact that a man, receiving through his sense of hearing or sight another man's expression of feeling, is capable of experiencing the emotion which moved the man who expressed it. To take the simplest example: one man laughs, and another, who hears, becomes merry; or a man weeps, and another, who hears, feels sorrow . . . And it is on this capacity of man to receive another man's expression of feeling, and experience those feelings himself that the activity of art is based.

(Leo Tolstoy. Aylmer Maude, trans. What Is Art? Bridgewater: Baker & Taylor, 2000. p. 48)

Tolstoy's way of describing art seems like a set up for a scientific experiment.

A scientific approach to art is not new. Many artists, most notably those of the Renaissance, approached art with a rigorous scientific mindset. The fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Italian schools of painting, especially in Florence and Rome, were concerned with geometry and the Golden Mean and were epitomized by the works of Leonardo Da Vinci and Raphael. European artistic training and up until the end of the nineteenth century, included classes in geometry and scientific theory. Impressionist and Divisionist artists, though rejecting traditional art, embraced new discoveries in color theory. In the twentieth century, the Futurist art movement applied current scientific understanding to effectively portray speed and movement on a canvas. Rothko was intensely concerned about the affect of color on the brain and was concerned about where his paintings would hang in case they would have an adverse results on the viewer (e.g. he believed that red was good for dining areas). I could think of a number of other examples.

The point is: science and art have been bedfellows for some time. So, it follows, why don't we use science to futher improve our understanding of art?

In 2004, Dr. Zeki and his colleague Dr. Hideaki Kawabata published a study titled Neural Correlates of Beauty in the April 2004 J Neurophysiol journal of the The American Physiological Society. The study reports on an experiment where ten woman, with at least one college degree, were asked to rate paintings on a scale from 1 to 10, 10 being beautiful and 1 being ugly. (Note that the test controlled for a subjective experience with each painting, allowing personal preference and not scientific judgment to intervene.)

Each woman was placed in an MRI scan and, then, shown the paintings they rated in random order. The brain patterns of the women were mapped to determine whether or not the brain has has beauty or ugliness centers.

The conclusion of the study states:

The results show that the perception of different categories of paintings are associated with distinct and specialized visual areas of the brain, that the orbito-frontal cortex is differently engaged during the perception of beautiful and ugly stimuli, regardless of the category of painting, and that the perception of stimuli as beautiful or ugly mobilizes the motor cortext differentially.

(A PDF of the the full, published study, along with other studies by Dr. Zeki, can be found on the Wellcome Institute's website: neuroesthetics.org/research.php.)

In other words, setting aside a personal interpretation of beauty, the brain has established neuro-pathways that are triggered when looking at a beautiful or ugly work of art.

As the field of Neuroesthetics expands it may eventually influence the art world. As an art historian, I am curious about what makes a work of art or an artist have a lasting impact. To find out art theorist often uses a highly subjective and, therefore, uneasy mix of soft science. Having a more scientific approach to what makes a painting work, would be a welcome tool in my belt.

The effect of this kind of research on working artists could be useful or damaging, depending on the intent of the artist. If an artist wants to learn what affects her work is having on her viewers-- and, therefore, understand how to better hone those intended results--it seems very useful to use the ideas supported by neuroethetics. On the other hand, the last thing I would want to purchase it market-tested works of art. Thankfully, this doesn't seem to be the intent of Dr. Zeki's work.

Dr. Zeki has a blog, which he regularly updates: profzeki.blogspot.com. As the founder and leaders of the field of Neuroethetics, it is a good place to learn about his latest thinking.