Visiting the Annual Olympia International Art & Antiques Fair (June 5-15)

Cane dealer and scholar, Geoffrey Breeze, showing me one of his favorite canes currently on show at Olympia.

"You do not carry a cane. You wear a cane." The foremost English cane dealer, Geoffrey Breeze, told me. At the time, he was holding a late-eighteenth-century English cane with an extending metal blade. ("I'd rather wear it than have it wear me," was the running commentary in my head.)

It was just one of many fascinating things--and equally fascinating interactions--I had at this year's Olympia Fair.

A view of the Fair from the upper level.

Olympia, as it is commonly referred to here, has taken place every June for 30 years. Dealers in fine and decorative arts gather from around the world to showcase their best works. The range of objects on view is enormous.

Before the fair opens to the public, dealers are required to submit their pieces to a vetting process. As a result, only items of a certain quality are available for sale. This means that no one is likely to find a diamond in the rough; but, it also ensures visitors see mostly diamonds.

Gilt-wood English pier glass (c. 1770) together with a French Louis XIV gilt-wood bed (c. 1870) from Butchoff.

I oppose the idea of putting a French Louis XIV bed, with its weightier, more muscular carving together with a playful, English Rococo mirror, but it's hard to resist all the glitter they create together. Of the two, the mirror is the more impressive.

This is one of three magnificent mirrors on show at Butchoff. There is growing trend of collecting mirrors. To the average person, it may be hard to put a mirror in the same category as high art. Cheap and ready access to mirrors in almost any home furnishing store diminishes our expectation of them. However, these mirrors were some of the most expensive and luxurious items of their day.

The mirror above was either the product of or heavily influenced by the designs of Thomas Chippendale's Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker's Director, published in 1755 (First Edition). It was likely made in the last quarter of the eighteenth century.

Chippendale was influenced by imported Asian art, especially lacquer and ceramics that depicted scenes of scholars, Buddhist temples, dragons, and plants, little understood but copied by European ceramicists, textile makers, and furniture designers.

By the 1800, glass technology had not progressed to the point where a large, continuous sheet could be made. The process of making even small panes was expensive and time consuming and required the use of dangerous chemicals like lead and mercury.

The above mirror appears to consist of at least six panes, which are cleverly separated by gilt wood carving.

I know very little about the painter Bridget Riley. Over the past year, Riley's paintings have been increasingly seen in fairs and art galleries throughout London, but usually on a smaller scale that make the works look like creative bar codes. Not usually a fan of non-traditional painting, I was drawn to this work. (I literally saw it from across a room and, ignoring everything else, walked until I was standing in front of it.)

The combination of its large scale and tiny, multi-colored lines made this one of the most pleasant and--perish the word!--interesting paintings I have seen. (For a complete discussion on why "interesting" is a poor word for art criticism, read Leo Tolstoy's What is Art? I'll post on it later.) Riley's paintings are all done by hand, not by machine. Up close, it would be fair to call them painterly, as each stroke is visible. The execution of the piece reminded me of the Russian Suprematist work Black Square (1915) by Kasimir Malevich, who painted simple geometric shapes by hand.

The testosterone emanating from this booth had me quoting Theodore Roosevelt the rest of the day. ("Bully!") Carved elephant tusks to either side of the marble bust, a narwhal tusk lying on the table, sea turtle shells . . . all in front of the manly backdrop of chains.

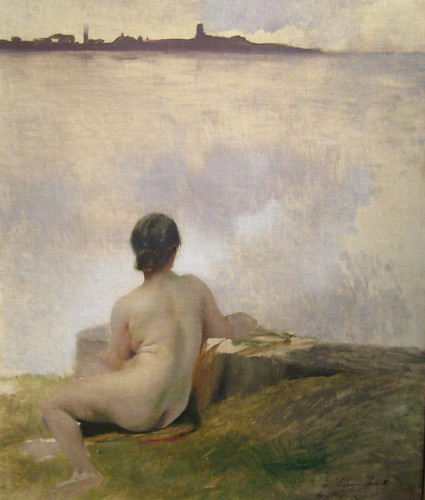

Albert Besnard (1849-1934) Nude Looking Out to the Sea (1885), oil on canvas, 21 3/4 BY 18IN. (55 BY 46CM.) Available from Constantine Art.

This was my favorite painting from Olympia. Though not the most important work--I'm sure it was little noticed by most people--it is a beautiful, meditative painting.

Besnard's father studied under Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and Besnard himself studied in the studio of Alexandre Cabanel. By age 19, Besnard was already showing works in the Salon.

This work is part of a tradition of nymph paintings, which were popular during the 1870s and 1880s. Perhaps the most famous work in this category is Opal (1881) by Anders Zorn. The paintings usually feature a nude, other-worldly woman in a natural setting.

The result is usually boudoir and mildly-erotic. But the effect of this painting is not sexual; it is full of melancholy. I found myself looking over her shoulder into that large abstract expanse with a kind of contentment I haven't felt from a painting in some time.

On a less-serious note, what English antiques fair would be complete without an Admiral Lord Nelson enamel snuff box? Yours for a mere £300 (about $600) from the Antique Enamel Company.