Note: Right now there are two remarkable exhibitions taking place: The Sacred Made Real, about religious Spanish sculpture, a loan of John Singer Sargent’s painting The Children of Darley Bolt (1882) to the Prado Museum, where it hangs next to Velázquez’s Las Meninas (c. 1656). I know I have written about Eakins and Velázquez before, but I haven’t been able to stop thinking about the Spanish Master’s influence on nineteenth-century artists. For me it is a source of endless curiosity and one of the more unexplored aspects of the period.

When John Singer Sargent travelled to Spain in 1879 his approach to painting fundamentally and irrevocably changed. There his understanding of painting was forever infused by the restrained palette, virtuosic brushwork and reverence for nature learned principally from Diego Velázquez (Spanish, 1599-1660).

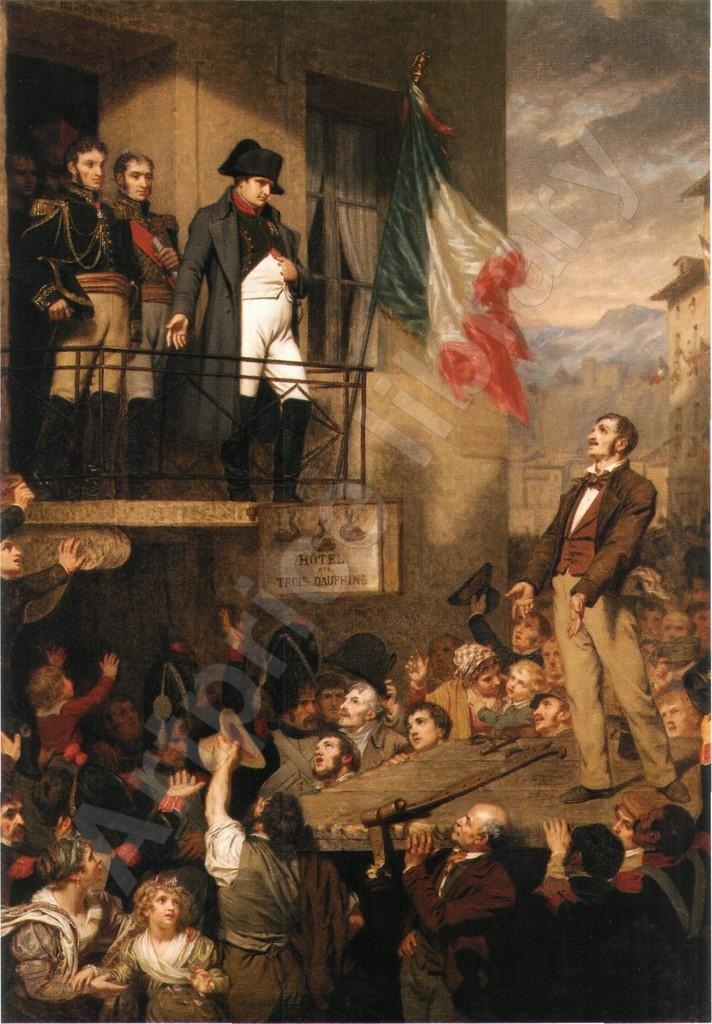

Sargent travelled to Spain at a time when France, the center of the international art world, had rediscovered Spanish masters. King Louis-Philippe’s Galerie Espagnole (1835-1853) and the marriage of Emperor Napoleon III to Eugenie Contador, a Grandée of Spain (1853), brought a newfound appreciation to the Spanish Golden Age and its artists that excited a generation of artists working in Paris.

Édouard Manet, Léon Bonnat, Jean-Léon Gêrome, Thomas Eakins, Julian Alden Weir, William Merritt Chase, and many others travelled to Madrid to copy works found almost exclusively in the Prado Museum. Chief among the artists copied by foreigners was Diego Velázquez, considered a new, viable alternative to French classical models that dominated Academic painting.

Sargent was a student at the prestigious and exclusive École des Beaux-Arts, when his instructors Carolus-Duran (French, 1837-1917) and Léon Bonnat (French, 1833-1922) suggested that his development as an artist would improve dramatically from a visit to Spain. Sargent visited the Prado Museum multiple times from October to November in 1879. The official Registry of Copiers records Sargent copying The Crucifixion (c. 1632), Las Meninas (c. 1656), and Las Hilanderas (c. 1644) by Velázquez.

As court painter to Philip IV of Spain, Velázquez was employed by the most powerful country on earth. However, unlike many other Baroque painters of his time, whose grandiose works were showcases of extravagant colors, exotic creatures, and obscure subjects,Velázquez’s work features everyday people in everyday settings. Even his few religious and mythological works are notable for not idealizing their subjects.

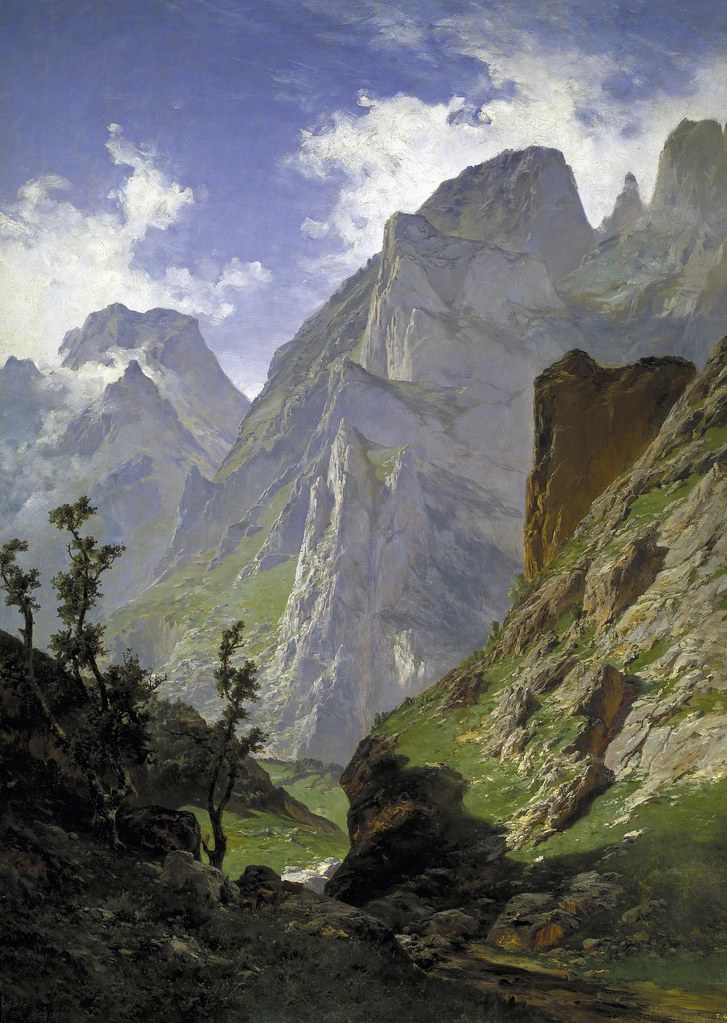

The French discovery of Velázquez came at a time when artists were breaking from a long-standing tradition of Classicism, which shunned Realism in favor of idealized subjects and painterly technique that obscured the artist’s hand. In Paris, Sargent’s education was considered the best in the world. It emphasized compositional formulas based on the Greco-Roman tradition as interpreted by French masters such as Nicolás Poussin (French, 1594-1665) and, later, Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748-1825). Their approach to art required rigorous draftsmanship that often resulted in statuesque, figures in classical landscapes or architecture. This interpretation of classicism was the official style in Europe for nearly 300 years. The rigidity of Academic painting limited the kinds of subjects artists could produce for competition and patronage.

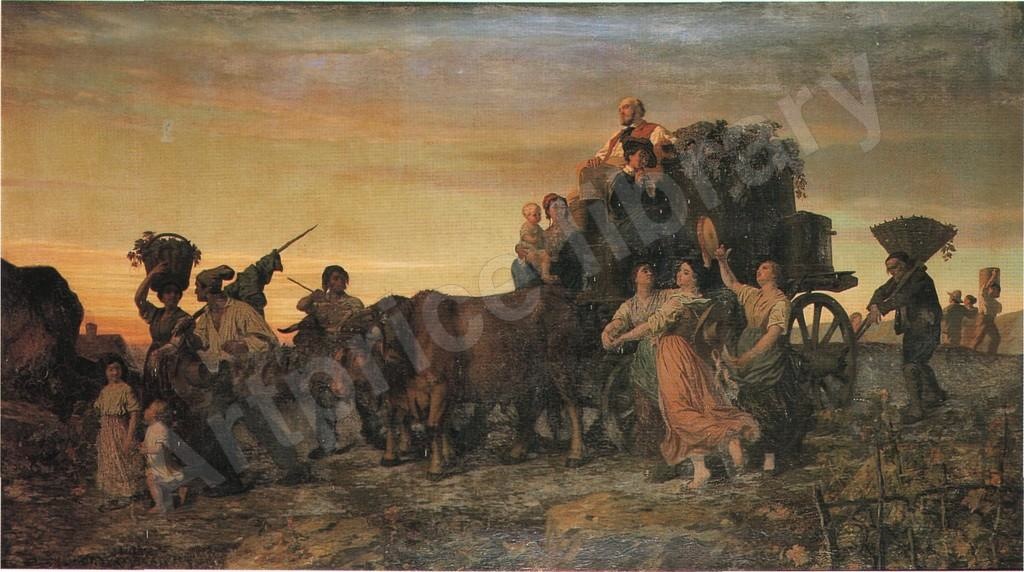

When Louis-Philippe opened his Galerie Espagnole in 1835, works by Velázquez, José de Ribera (Spanish, 1591-1652) and Francisco Zurburán (Spanish, 1598-1664) were introduced to the French public for the first time. Working at the same time as the founding fathers of French art, these Spanish artists offered an alternate classicism that emphasized nature.

The study of Velázquez’s work changed a generation of French artists’ approach. Unlike many Academic painter, Velázquez was unafraid to leave distinguishable brushstrokes on his canvases. Thick strokes of paint are clearly visible, demonstrating both his virtuosic skills–capable of reproducing an astonishing array of textures–and making the painting more of a three-dimensional work. His palette is limited, almost exclusively earth tones. When Velázquez did use color, it was muted, rather than garish; and, therefore, subjects appear more lifelike. Whether painting mythological figures, royal portraits, or multi-layered religious narratives, Velázquez captures the natural surroundings and features of his subjects without idealizing them. As a result, he exalts and dignifies the truth while simultaneously making them more approachable.

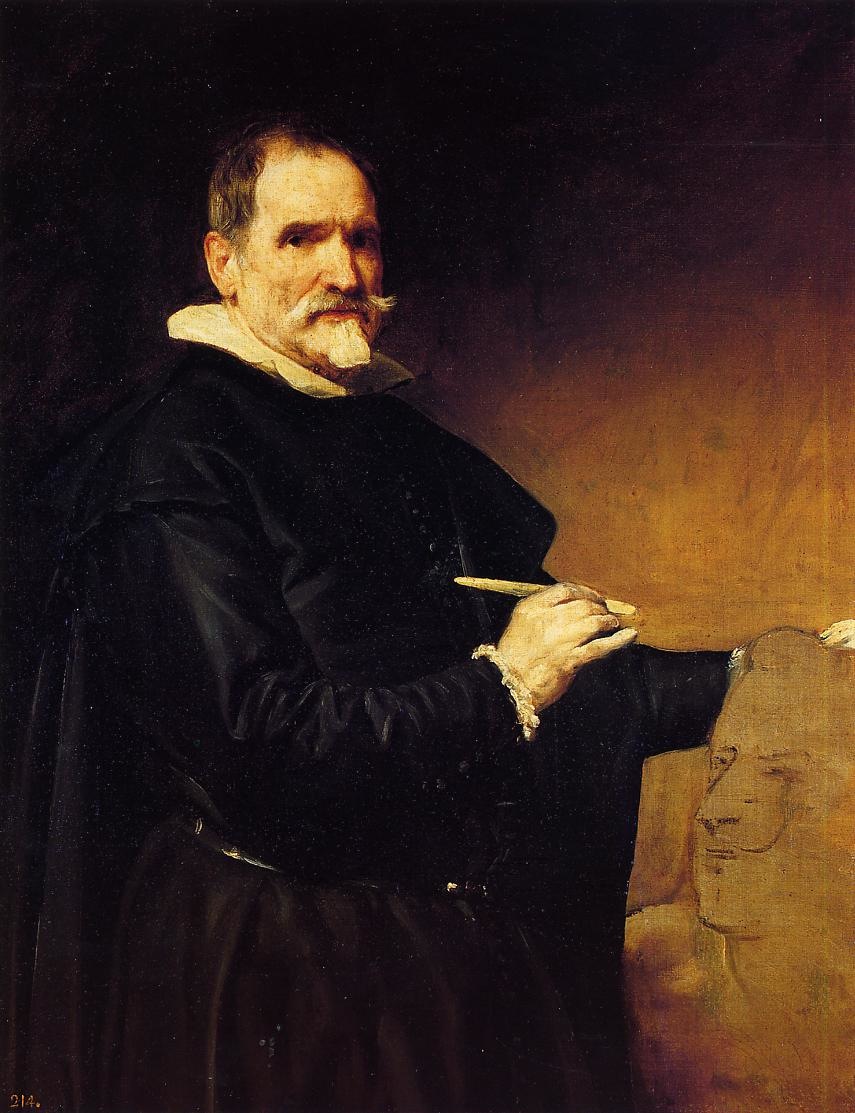

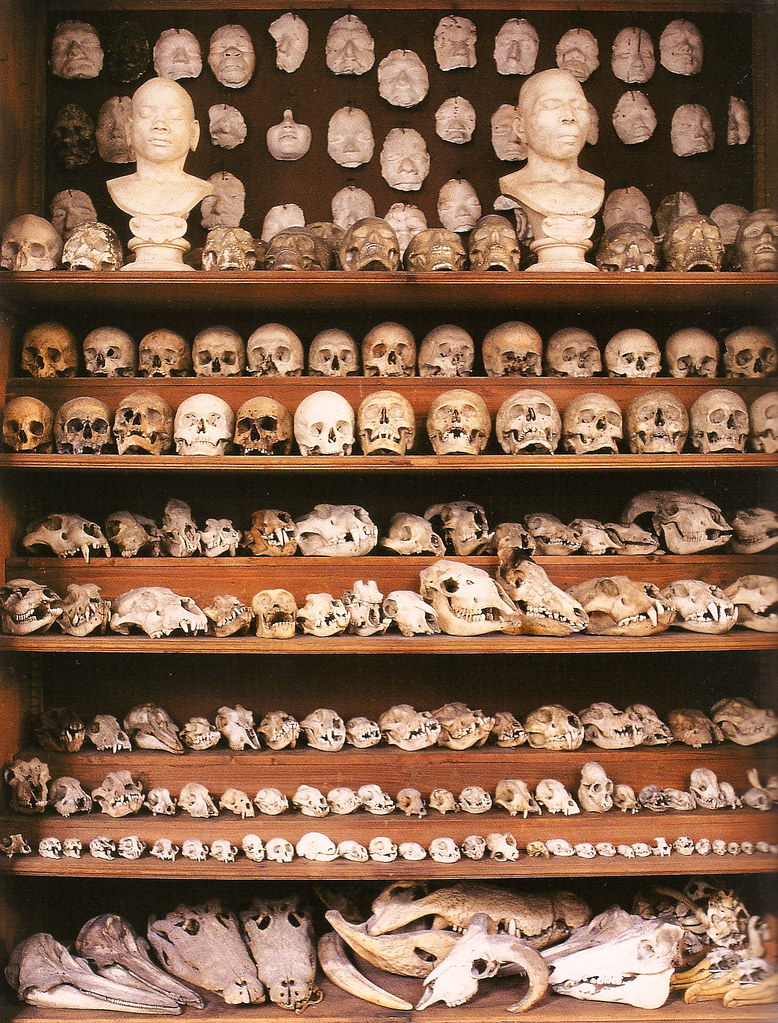

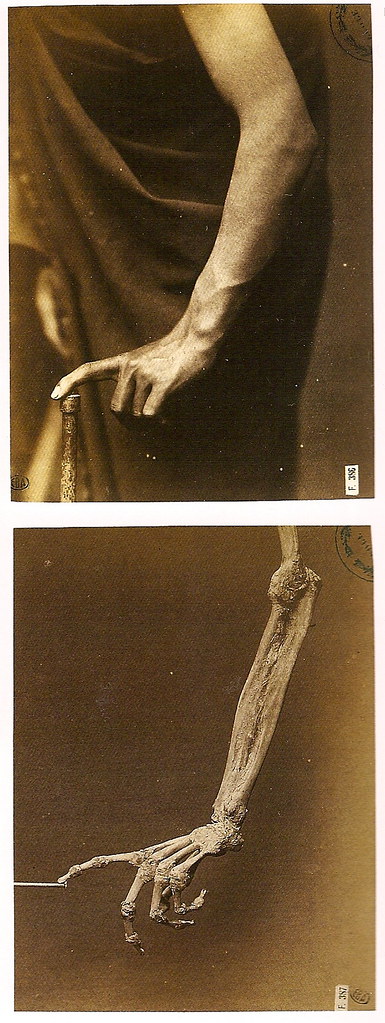

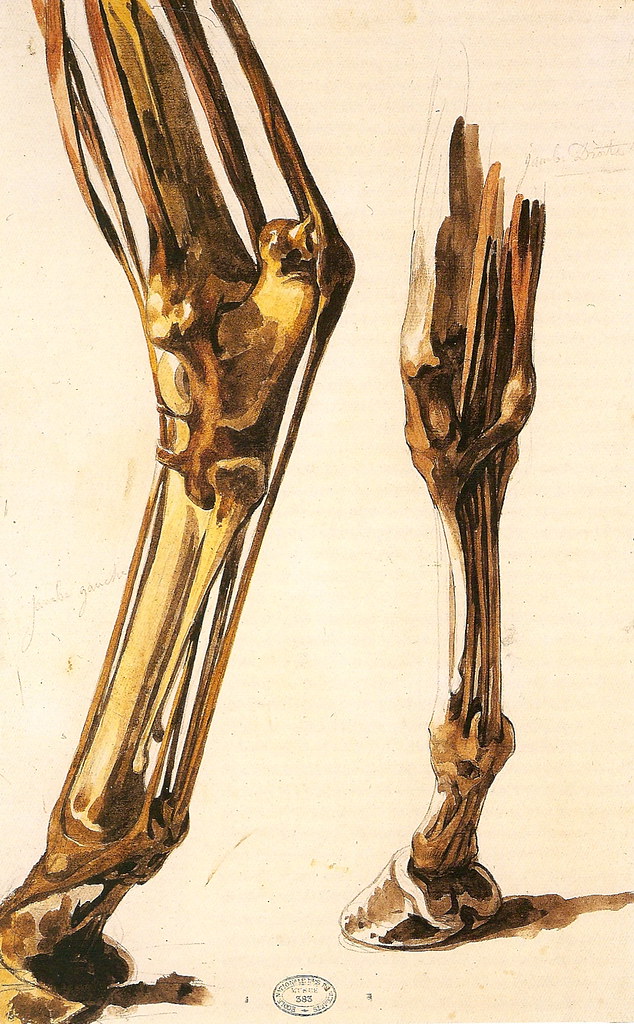

In Crucifixion, Sargent paints one of Velázquez’s most repeated subjects: the crucified Christ. It is important to note that, rather than the actual cricified Christ, both Velázquez and Sargent painted wooden crucifixes. Velázquez was influenced and mentored by the Spanish sculptor Juan Martínez Montañés (1568-1649).

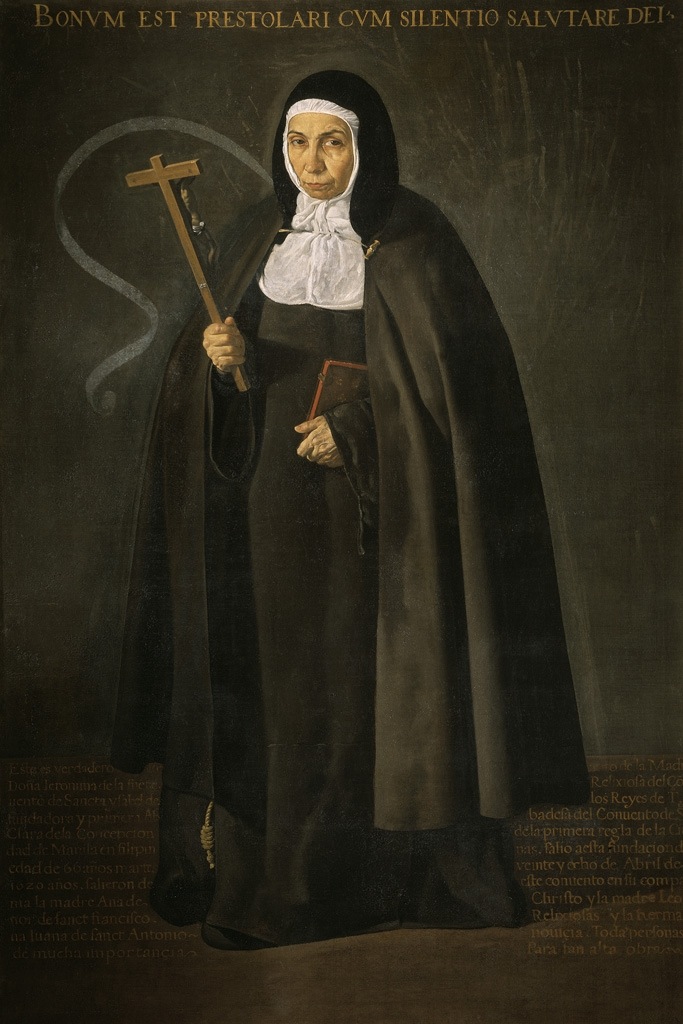

Known as the Michelangelo of wood, Montañés created hundreds of religious sculptures that are still in use in religious festivals. The crucifix in Velázquez’s La venerable madre Jerónima de la Fuente (c. 1620) and Sargent’s Crucifixion are both based on Montañés models.

In his Crucifixion, Sargent captures a private moment of meditation on Christ’s sacrifice. The crucifix hangs on a chapel wall while light streams from an upper window.

Using a wooden crucifix, rather than a realistic Christ, emphasizes the religious experience of the viewer, rather than Christ’s experience on the cross. This is a meditation on what reflecting on the crucifixion means to the viewer well after the event has taken place. Sargent capitalizes on this reflection by using Velázquez’s technique of broad visible brushstrokes. This allows the mind of the viewers to fill in the details and, therefore, participate in the subject in a way that incites the imagination like no detailed rendition could. Sargent also adopts Velázquez’s use of ochres. The nearly monochrome palette draws greater attention to Sargent’s remarkable brushwork, which like Velázquez, is unabashedly visible, at times broadly defining Christ figure and at others using miniscule strokes.

These hallmarks of Velázquez’s technique were studied and absorbed by Sargent. He transmuted them into his own French education and used the two to become the world’s most sought-after portraitist and, arguably, the greatest American painter of the nineteenth century.