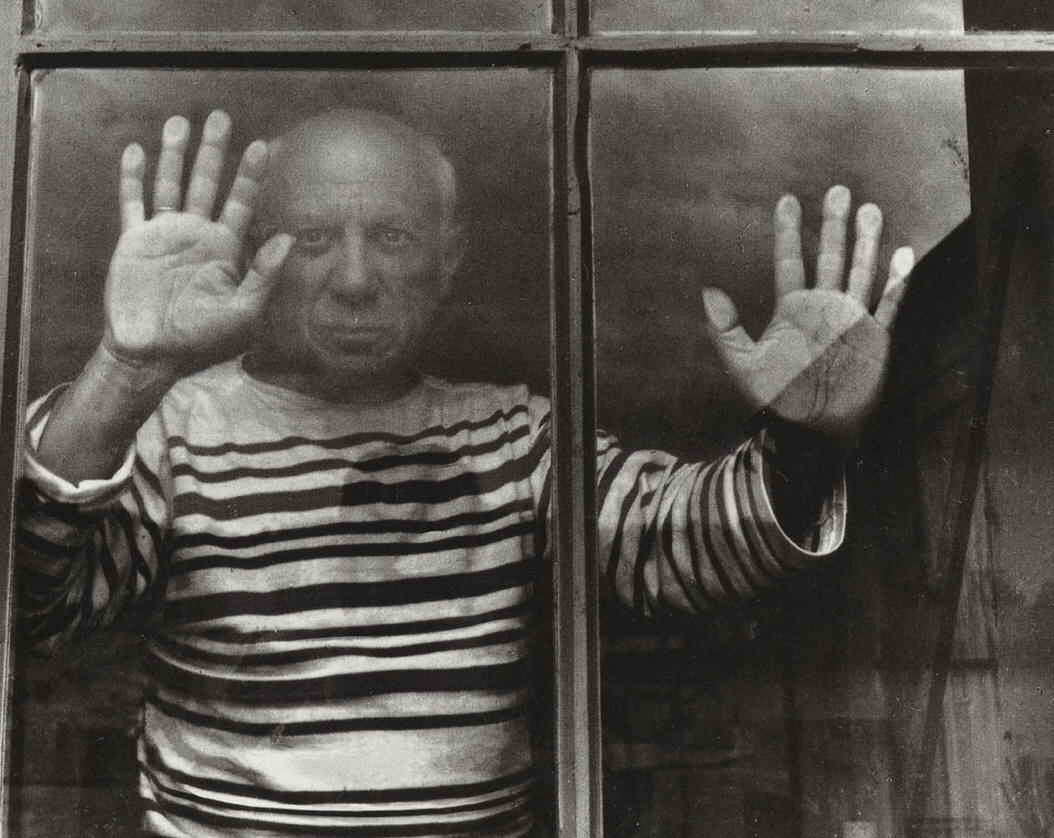

Picasso in London: "Not a Slave to the Canon"

After seeing The Raft of the Medusa by Eugène Delacroix (French, 1798-1863) Théodore Géricault (French, 1791-1824), a friend recorded Picasso saying: "That bastard! He was good."

The exhibition, Picasso: Challenging the Past, currently on show at the National Gallery in London, is a well-documented testament to the artist's admiration for artists that he made posthumous collaborators in his work, among them Goya, Velázquez, Poussin, Ingres, and El Greco.

Lest visitors think that Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973) had betrayed or diluted his innovative impulses, the introductory paragraph to the exhibition--boldly written on the wall near the entry--states "he certainly was not a slave to the canon." Thus, a confusing tone was set, turning up throughout the exhibition, that simultaneously attempted to admire Picasso's admiration for "traditional" artists while, in some cases, denying them admiration.

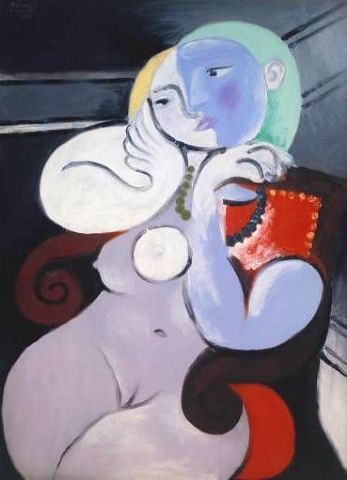

An example was the exhibition's treatment of Ingres. Making a comparison between the National Gallery's Portrait of Madame Paul-Sigisbert Moitessier by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (French, 1780-1867) to Picasso's Nude Woman in a Red Armchair, the exhibition claimed that Ingres, like Picasso "idealized eroticism," and that "the more one looks at Ingres, the less plausible his work seems." According to the film accompanying the exhibition, Ingres' arms and fingers appear to have no bones, and figures seem dramatically out of distortion, as if they were anticipating Picasso's work. It seemed like revisionism. (See my previous post on Ingres' careful attention to the human figure.) It was as though Ingres could not be appreciated on his own terms, but only on Picasso's.

Seeing Picasso's works, I don't necessarily think that he would have shared this perspective. There is no denying the copious amounts of time he spent reworking Diego Velázquez's (Spanish, 1599-1660) Las Meninas or the Rape of the Sabines by Nicolas Poussin (French, 1594-1665). This is what makes Picasso great: his simultaneous departure from and use of classical themes. As I walked through the exhibition I was remineded of F. Scott Fitzgerald's comment: “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” Despite the startling variety of his output--one piece reflects his classical training, another is nearly completely abstract, a work full of color, and another nearly void of spectrum--Picasso confidently comes across in each painting.

The exhibition seemed organized for those who already love and acknowledge Picasso as part of the canon. As such, it was, at first, difficult for me--someone who still struggles to relate to his works--to approach. However, the more I looked directly at the works, the more approachable they became. Despite the exhibition's sometimes revisionist treatment of "the canon," it was an ideal primer to his oeuvre. Deciphering Picasso's translation of Las Meninas by Velázquez, for example, kept me occupied for at least 30 minutes and provided numerous insights into Picasso's pictoral devices. It was a Rosetta Stone for Picasso.

A mentor of mine is fond of saying that "art is very personal." Personally, Picasso is a shock to my natural inclinations. However, I admire his genius and, with the help of this exhibition, found myself thinking: "That bastard! He was good."