There is a growing phenomena of painting and sculpting studios working to resurrect models of art education from the past. Some of the schools I am thinking of include the Grand Central Academy of Art in New York, The Florence and Angel Academies of Art in Florence, and the Los Angeles Academy of Figurative Art in California. There are many more. As an enthusiastic supporter, I have come to know some of the artists who have founded and attended some of these schools. In almost every case, these artists refer to a handful of foundational books that have influenced their approach.

The bible of most seems to be the late Albert Boime's book, The Academy and Painting in the Nineteenth Century. In it, Boime takes bird's-eye and ground-level views of studio practice in the French Ecole des Beaux-Arts from its foundation in the seventeenth century to its height of influence in the nineteenth century. It is a foundational text and deserves a great deal of attention.

Those who have read Boime's work may be surprised at how many different classical academic models there were in the nineteenth century and before. Knowing the plurality of approaches and their strengths and weaknesses may help anyone attempting to reinstate aspects of the classical tradition today.

Throughout the next year, I hope to explore various models of classical arts education. Today, I begin with the Academia dei Desidorosi, credited with being the first art academy to include life drawing a regular part of its curriculum.

The Academia dei Desiderosi (roughly translated as "those desiring perfection") was founded in the Northern Italian city of Bologna by brothers Agostino (1557-1602) and Anibale Carracci (1560-1609) with their cousin Ludovico (1555-1619). From the late-sixteenth to the early seventeenth centuries, the Desiderosi was a training ground for some of the the period's most influential painters, including Guido Reni (1575-1642) and Francesco Albani (1578-1660). Drawings produced by the Academia and its artists were highly sought after by other academies. In fact, many were collected and used for instruction by the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

At the time, Bologna was small, but influential. A rich agricultural center, it also had one of the oldest universities in Europe. The Carracci brothers were unusually well-educated at a time when most artists were illiterate and considered craftsmen. Both Agostino and Annibale had begun legal training before setting it aside for art. They could read and write and had a good working knowledge of Latin. Agostino, especially, was well regarded for his understanding of philosophy, poetry, mathematics, and, even, mechanics (e.g. clocks and machines).

The Academia dei Desidorosi claims among its members some of the most important painters of the time, including Guido Reni (1575-1642) and Francesco Albani (1578-1660). Unlike many nineteenth-century academies, the Desidorosi did not draw a distinction between teachers and pupils. Instead, the Carracci considered themselves first among equals and participated in all exercises. The Desidorosi only accepted experienced artists. Most members were in their mid-to-late twenties. This approach differed from most studios and academies of the time like the older, well-established Roman Academia di San Luca, which accepted students as young as eight years old.

The study of the human figure was central to studies at the Academia dei Desidoerosi. Until the nineteenth century, life drawing was almost exclusively done with male models. The use of female models was considered immoral, and in most of Italy, Germany, France, England, and Spain, was illegal. Instead, artists relied on classical statuary, contour drawings of the female figure or simple substitution of the male for the female. (Some attribute the masculinity of of Michelangelo's women to the lack of female models, believing that he and others simply put breasts and long hair on the male form. Though, I believe this is an oversimplification, it may have some truth.)

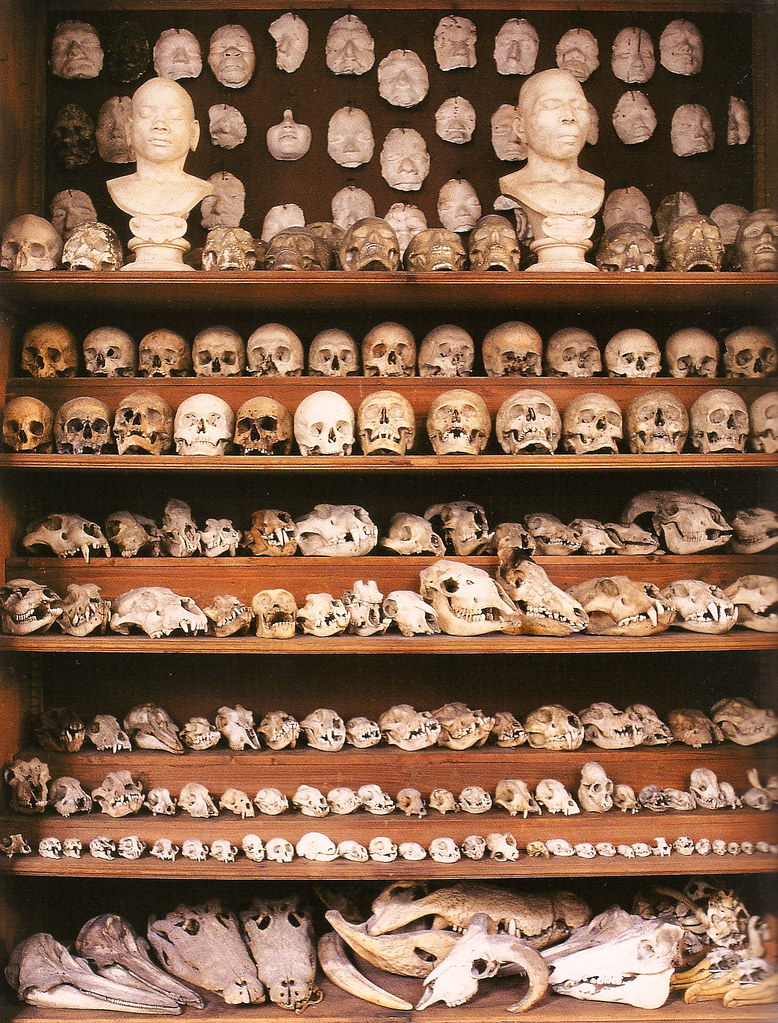

Live models were hired. But, also, students posed for one another. In some instances, the Carracci brothers took the then unusual step of inviting a "Dr. Lanzoni"--little is known of his real name or role in the community--to dissect corpses for the benefit of students. (Autopsies of the rich and noble were then common as a way of assuring the cause of death was not foul play.)

In addition to live models, the Academia used drawing books and examples from the Antique (Greco-Roman statues, reliefs, coins, and architectural drawings). According to Gert-Rudolf Flick:

The Carrracci also relied on the use of drawing-books for instruction, a format that subsequently became fashionable in its own right. Most of these drawing-books were produced by professional artists, and reflected current studio practice and art theory. A drawing-book can be defined as a pedagogical work in which the visual instruction dominated the verbal, and is thus quite different from treatises such as Alberti's De Pictura or (more obviously) Vasari's Vite, or even from anatomical texts and books on perspective. The drawing-books in question contain numerous sheets filled with parts of the human body such as ears, noses, legs, and feet, depicted from different points of view: front, three-quarter and rear. (Gert Rudolf-Flick. Masters & Pupils: The Artistic Succession from Perugino to Manet, 1480-1880. London: Hogarth Arts, 2008. p. 106-107)

Agostino Carracci had a large collection of busts, statuettes, Old Master drawings, engravings and contemporary medals that students were allowed to copy and study.

Studies were not focused exclusively on the human figure. The Desidorosi believed that the overall goal was a closeness to nature, which was defined more widely as humans, animals, plants, and the rules of architecture.

Certain hours were set aside for theoretical questions, perspective and architecture, all of which Agostino was especially adept at demonstrating in condensed form in a small number of maxims as can be seen in some of the writings by him that I have in my possession. (Gert Rudolf-Flick. Masters & Pupils: The Artistic Succession from Perugino to Manet, 1480-1880. London: Hogarth Arts, 2008. p. 111)

Regular visits to the countryside where paintings and drawings were made directly from nature. For studies in perspective and architecture, the Carracci relied on Sebastiano Serglio's Libri di Architectura (a pdf of books three and four can be found online here) and trips to local churches and notable homes, guided by Agostino and local professors.

When in 1595 Annibale and Agostino were commissioned to paint the palace of Cardinal Odoardo Farnese, they left the Academia to the management of their cousin Ludovico. Some information is available on the Academia during this period, and it is evident that the brothers were the main force of Desidorosi and, without them, it did not have the same energy or longevity. The academy, while carried on by Ludovico and, then other students, never again attracted the same attention or produced the same quality of artists.

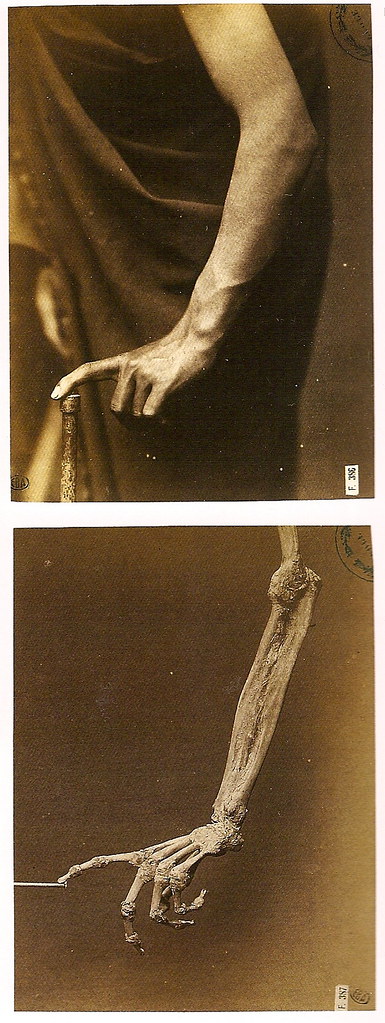

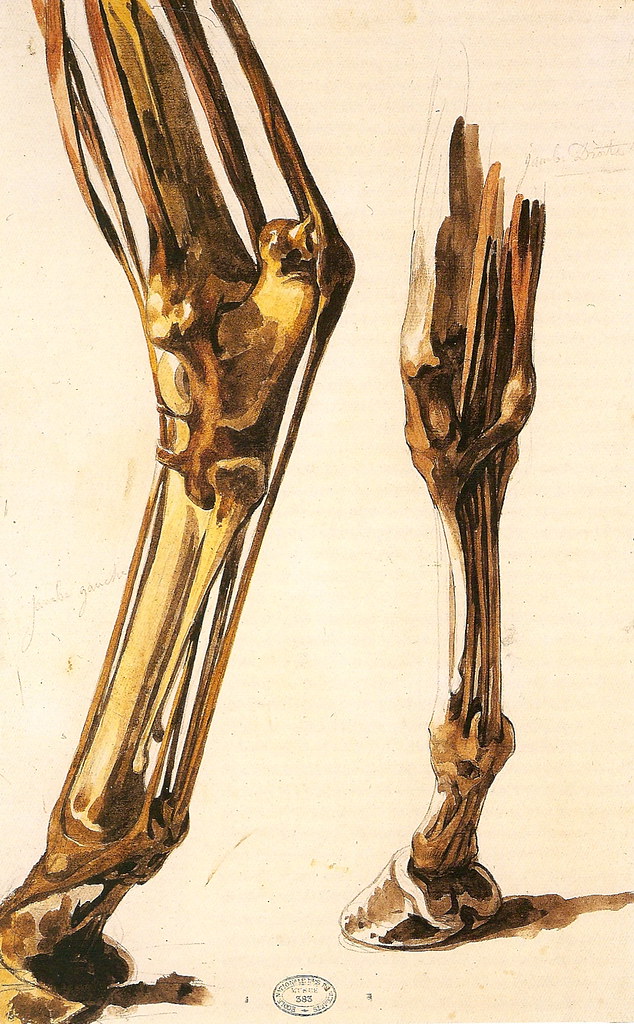

Occasionally, I come across a book that was made with me in mind. Figures du Corps: Une Leçon d'Anatomie à l'École des Beaux-Arts is the catalogue of the exhibition by the same name held from October 21, 2008 to January 4, 2009 at the l'École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris. (Painfully, I first learned about the exhibition after seeing this book in a bookshop window in London, which is either a testament to my own ignorance of events like this or a sign that marketing efforts had limited reach.)

Occasionally, I come across a book that was made with me in mind. Figures du Corps: Une Leçon d'Anatomie à l'École des Beaux-Arts is the catalogue of the exhibition by the same name held from October 21, 2008 to January 4, 2009 at the l'École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris. (Painfully, I first learned about the exhibition after seeing this book in a bookshop window in London, which is either a testament to my own ignorance of events like this or a sign that marketing efforts had limited reach.)