According to Victor Bardia, Feriarte is Europe's largest annual Fine & Decorative Art fair. Bardia is one of the event's principal organizers. I met him and his son, David Bardia, at their gallery, Victor I Fills, during my last trip to Madrid. At that time, Bardia extended an invitation for me to return for the Fair. I'm grateful he did.

According to Victor Bardia, Feriarte is Europe's largest annual Fine & Decorative Art fair. Bardia is one of the event's principal organizers. I met him and his son, David Bardia, at their gallery, Victor I Fills, during my last trip to Madrid. At that time, Bardia extended an invitation for me to return for the Fair. I'm grateful he did.

I've been to a number of fairs over the years and was skeptical Spain's fair could be larger than others. If it was, I assumed, it must be of lesser quality. Having walked at a casual pace for three hours, I thought I had seen all there was only to pass through a door that revealed another space, filled with more exhibitors and larger than the last. In total, I spent nearly eight hours on my feet, talking with dealers and collectors. For the most part, I was impressed by the quality of pieces, which were at least comparable, and often superior, to those of other fairs like Olympia or BADA in London.

Each dealer I met, with the exception of one--a German gallery that specialized in Russian and German turn-of-the-century art--was based in Spain. The majority of exhibitors had galleries in Madrid, Barcelona or both. Works at the fair, which ran from November 15 to 23, were overwhelmingly Spanish, or from former Spanish territories (e.g. The Netherlands, Naples) with small but impressive selection of works by Italian artists. There was a surprising dearth of Latin American and other foreign works of art, perhaps reflecting a lack of foreign buyers at this year's fair.

More than one dealer told me that compared to previous years, visitors were down by one half or two thirds. These are difficult times for art fairs and dealers. In other words, it was a buyers market. I was often surprised by low prices for objects and paintings that, less than a year ago, I had seen at much higher prices in the same galleries. For the occasion, dealers were bringing out their best pieces. The quantity of works was astounding--an art historian's dream.

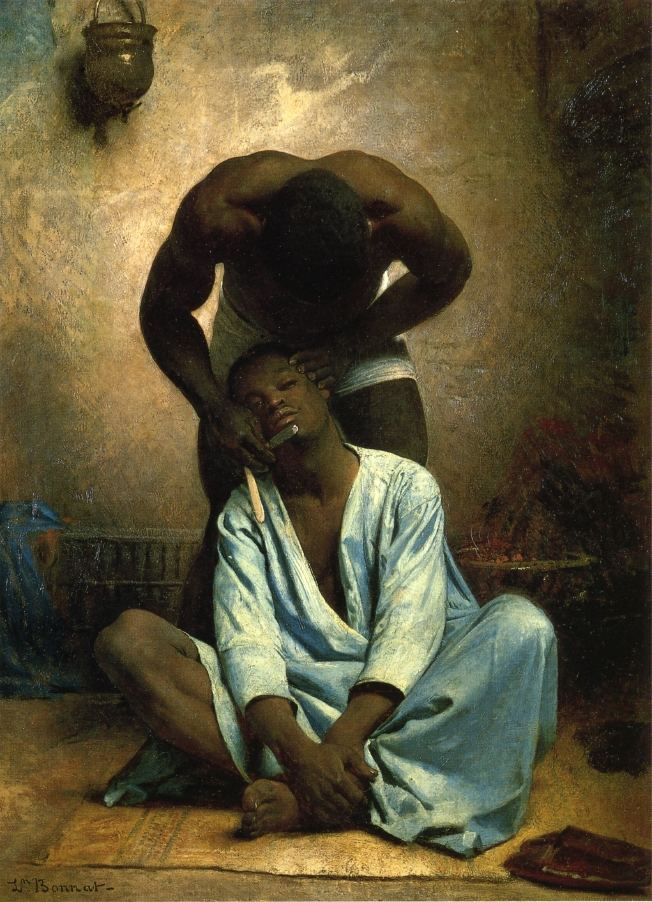

Two Laughing Girls by Borrell is a wonderful example of the kind of academic painting taught and practiced in late-nineteenth century Rome. Though Paris was undeniably the center of the art world a number of painters work and studied in the Eternal City.

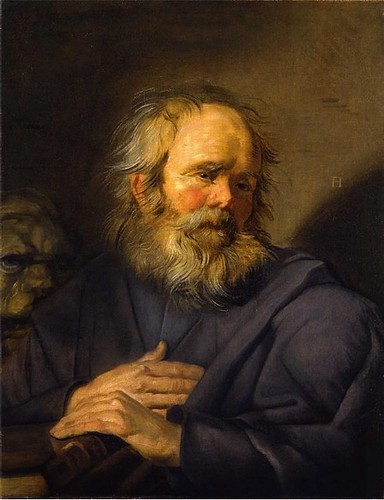

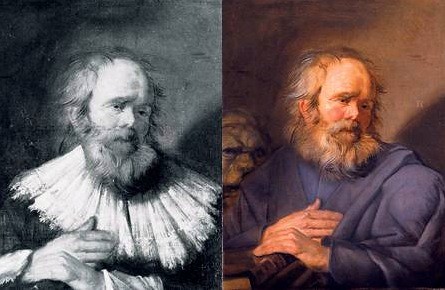

Borrell brilliantly draws the girls into our space by incorporating ornamentation from the neoclassical frame into the painting. The last two centimeters of the canvas are a combination of gesso and gold leaf over which he has painted one the two girls leaning her elbow on a Greek key patterned frieze. Seeing the piece, I wondered if Borrell had seen works by Dutch painters like Gerrit Dou, a contemporary of Rembrandt, who played similar visual tricks with his canvases.

With so many religious works, at times the fair seemed like a destination for pilgrims. God, the Virgin, and Saints were everywhere, covered in gesso, gold and pastel-colored oil paints. A number of the exhibitor's stall were set up as small houses of worship, with some even burning incense.

Spanish pieces like Christ crowned with thorns reflect skills brought the country by workmen from the Netherlands. Through the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, The Netherlands were Spanish territory. A number of Netherlandish artists moved to Spain, infusing a northern realism--as opposed to classical idealism--into Spanish sculpture and painting.

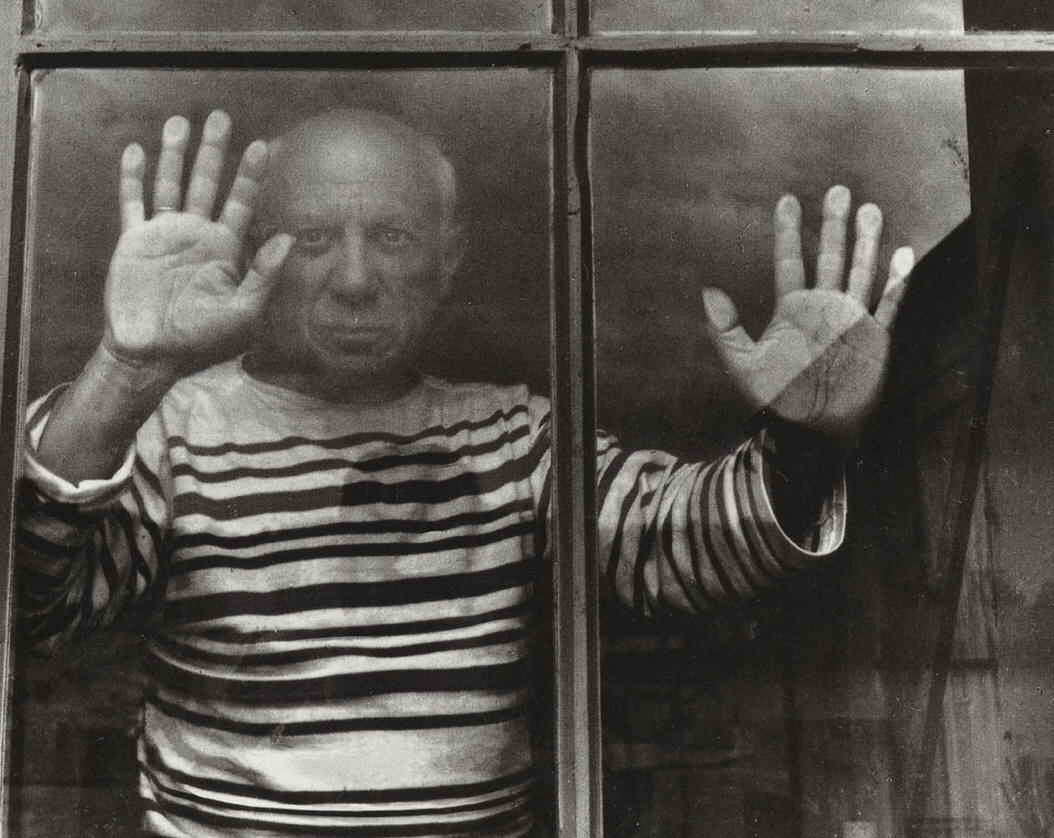

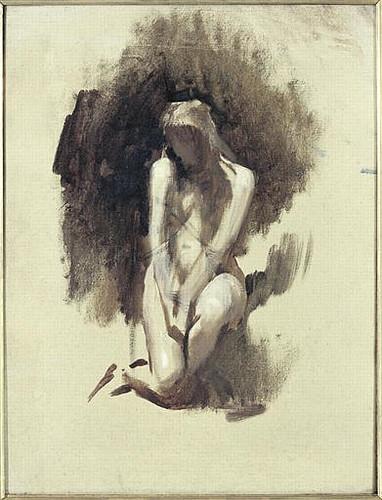

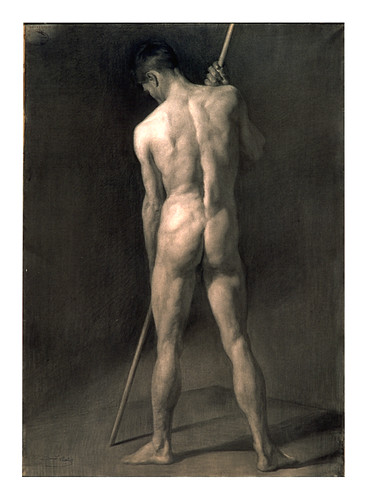

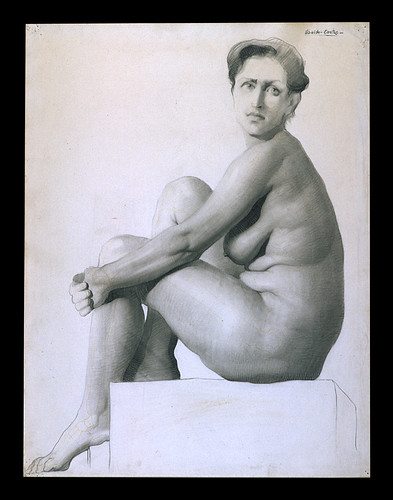

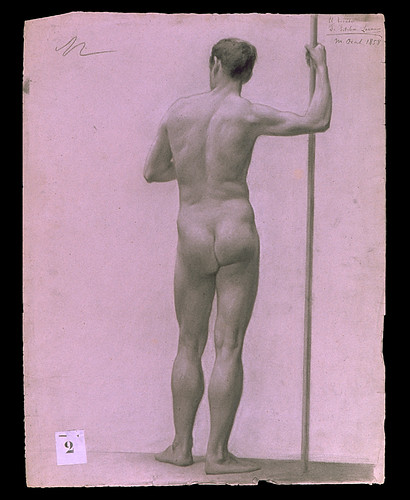

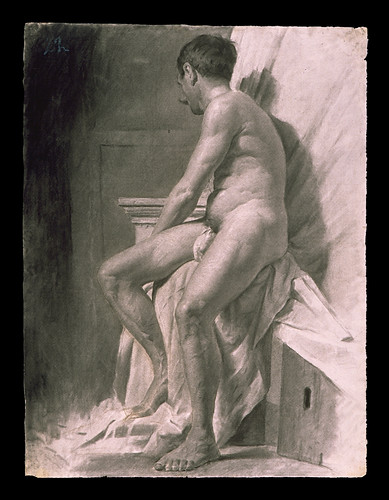

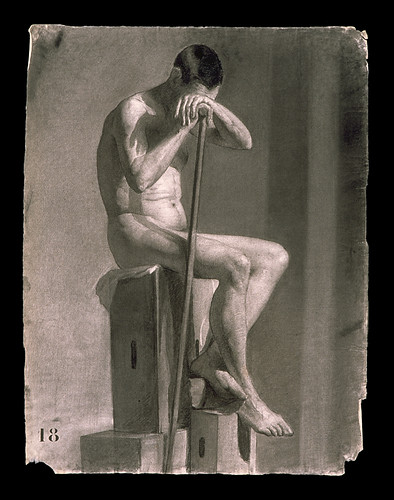

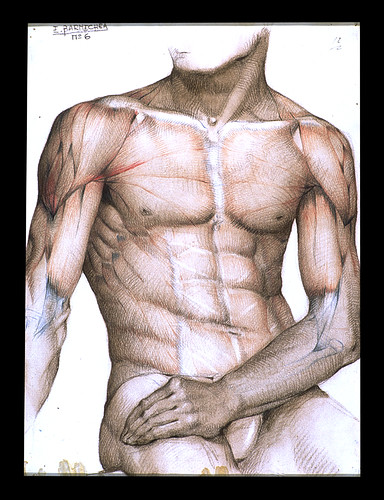

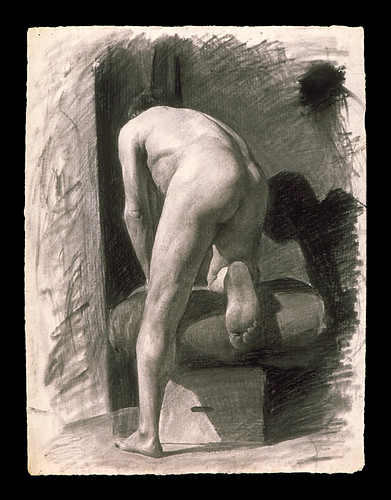

Having made his name in abstract painting and Cubism, some people are surprised to learn that Picasso was trained as an Academic painter. He studeid at the academy in Barcelona, where he produced a number of figure studies in charcoal and a few oil paintings. Some can be seen as the Picasso Museum, installed in his former home in Barcelona. His ability to accurately render the human figure, especially in chalk, is impressive.

I was surprised to see one of his academic oils available at the fair. The work is evidence of his early propensity towards breaking down objects into basic forms. The shadows in Torso of a Young Man are sharp, clearly delineating muscles and separating the figure from its background. To me, the head and the body appear to belong to different figures, which is, perhaps, a choice or, more likely, a reflection of his inexperience. (He was only sixteen when it was painted.)

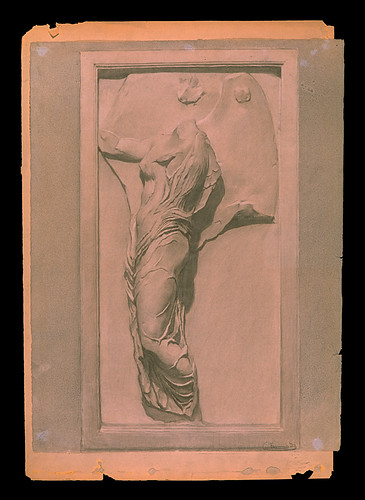

Once overseen by Julius Caesar and the birthplace of the Emperor Hadrian, Spain was one of of Rome's most important provinces. Besides the obvious inheritance of a Latin language, Spain retained a number of Roman works of art and architecture. A few Feriarte stalls were dedicated exclusively to ancient sculpture and architectural pieces (e.g. fountains, doorways).

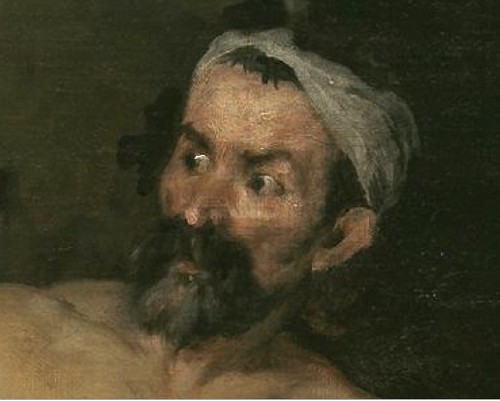

It's not every day that a Ribera could be yours. Considered one of Spain's greatest painters, Ribera's oeuvre is represented in nearly every major European museum. Ribera was born in Valencia but moved to Naples, which was a Spanish territory at the time. Naples was home to a number of influence painters, such as Giordano and Caravaggio, who established a taste for religious paintings with earthy, realistic people.

Many of Ribera's works are contemplative with figures deep in thought or asleep. In this, he has captured a fleeting moment, when the Saint receives his assurance of a place in heaven. Saint Jerome, a fifth-century compiler of the Bible, was a favorite subject of Ribera. (Maybe it would be more accurate to say Ribera's patrons loved the way he painted Jerome, making it a regular request.) I've seen perhaps eight versions of Saint Jerome by the painter. I was particularly taken by the brilliant light in this one. The arrival of the angel above Jerome's head brings light on the elderly man's torso. Up close, his chest and belly are a soup of oily paint that, despite their fluidity, are convincincly skin like.

Both this and the image from the previous post of a tree trunk in front of a rug were on display in the stall of Rica Basagoiti from Madrid. Once rugs were considered the most luxurious items in a collection. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Spanish and Dutch put rugs like these on their tables, rather than on the ground. Walking on them would have been considered the height of conspicuous consumption.

The display of these rugs by Rica Basagoiti seemed to return these rugs to a level of prestige that was appropriate to their era. In the above image, a large magnifying glass is placed several feet from the rug, making the richly-preserved colors jump out at anyone passing by.

Jiménez was a Spanish painter who had moved to Paris, where he regularly participated in the annual Salons--one of the few Spanish painters to do so. His work careful attention to detail and tendency to paint figures in period costume are reminiscent of the French painter Meissonier, who was popular in Paris at the time.

Though this is a small work, it shows off Jiménez's arsenal of skils and powers of observation. The figure seems to be well relaxed and effortlessly painted, but close inpection reveals countless tiny strokes. The light coming through the window casts a series of complicated shadows. I found myself wondering how much easier it would have been to have the light coming from a different direction or having the window at his front rather than his back.

By far, my favorite piece from the Fair was this German tankard, which stands nearly 25 centimeters in height. Made of several ivory sections seemlessly pieced together, it is a wonder of craftsmanship and artistry. Rather than discuss it at length, I believe a lengthy look at it provides a kind of refinement and appreciation beyond words. (Each image can be clicked for a much higher resolution image.)

For more pictures of the tankard, and a number of other pieces that I saw at Feriarte, visit my Flickr page.