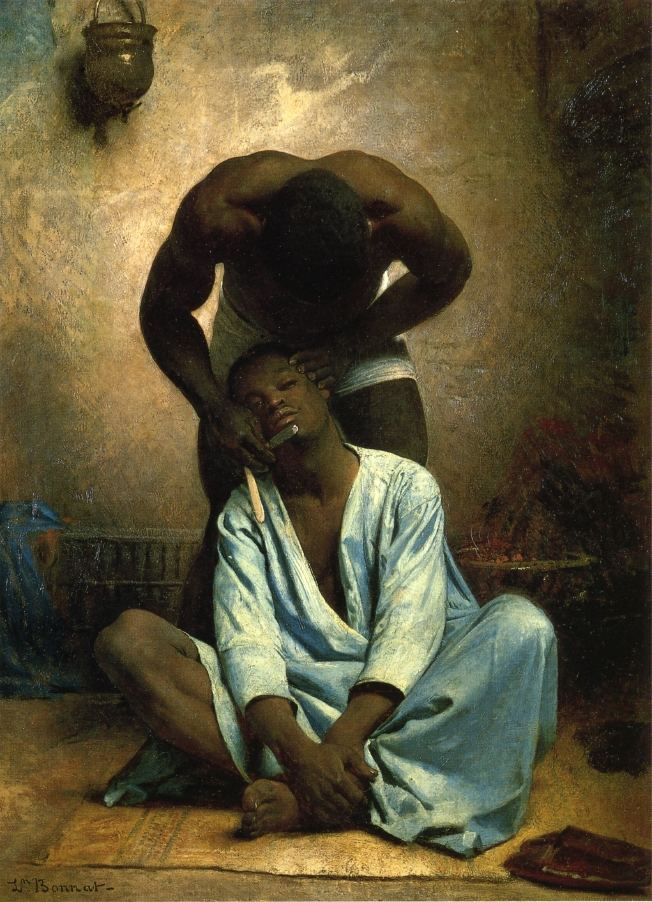

During the last quarter of the nineteenth century, few French painters have been as influential and forgotten as Léon Bonnat (1833-1922). He was trained in the Academic tradition and eventually became Director of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, yet he was a champion of controversial painters, such as Gustave Courbet, and a lifelong friend of Edgar Degas, who was closely associated with the anti-academic Impressionist movement. Trained in Madrid and Paris, he was a bridge between two artistic cultures, which he combined in his own work and his mentoring of a generation of painters that included Thomas Eakins and John Singer Sargent. His relationship with Spanish art would have far-reaching implications for nineteenth-century painting by legitimizing Spanish Masters, particularly Velázquez and Ribera, whose work had a great deal in common with French Realism in its depiction of the human figure.

During the last quarter of the nineteenth century, few French painters have been as influential and forgotten as Léon Bonnat (1833-1922). He was trained in the Academic tradition and eventually became Director of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, yet he was a champion of controversial painters, such as Gustave Courbet, and a lifelong friend of Edgar Degas, who was closely associated with the anti-academic Impressionist movement. Trained in Madrid and Paris, he was a bridge between two artistic cultures, which he combined in his own work and his mentoring of a generation of painters that included Thomas Eakins and John Singer Sargent. His relationship with Spanish art would have far-reaching implications for nineteenth-century painting by legitimizing Spanish Masters, particularly Velázquez and Ribera, whose work had a great deal in common with French Realism in its depiction of the human figure.

Because he destroyed all his own personal correspondence, what we know about Bonnat is usually gleaned from his students and the public records. In his wonderful book, The Revenge of Thomas Eakins, Sidney Kirkpatrick writes:

Bonnat went to great effort to capture the realism of this model, sometimes requiring his subjects to sit fifty or more times before completing portraits. The essential words to describe Bonnat’s paintings, as well as his reaching style--as more of his students reported--were “truth and logic.” . . . Bonnat’s personal struggles as an artist also resonated with Eakins. Writing to his father, Eakins related how Bonnat, as a young art student, had been deeply troubled by his teacher’s wanting him to paint the same way he did. Bonnat couldn’t oblige. “He was better than his teacher, although he [Bonnat] was doing such bad work [at the time],” Eakins went on. “His teacher told him he would have to stop painting, and then he went to [another teacher who] . . . told him to go and be a shoemaker, that was all he was fit for. A few years more and he was as big as the biggest of them."

Bonnat was born to a middle-class family in Bayonne. In the border region near Spain, the city is in traditional Basque territory. Bonnat’s family, in particular, was comfortable enough with Spain to make a move to Madrid in 1847, where his father opened a modest book store.

In 1837, the Prado Museum was opened to the general public and, later, enlarged as part of major redevelopment of the Madrid. Regular visits to the museum were compulsory for students of the nearby Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. There students were required to study Italian, Flemish, and Spanish Old Master works. Above all, and in order of importance, Velázquez, Murillo, Ribera and Zurburán--all well represented in the Prado’s collection--were considered models for nineteenth-century Spanish students.

Sometime between 1847 and 1855, Léon Bonnat was accepted and studied at the Academia. There he worked first under the instruction of José de Madrazo y Agudo (1781-1859), a student of Jacques Louis David (French, 1748-1825) and, then, his son, Federico de Madrazo y Kuntz (1815-1894), who had a life-long relationship with Jacques Auguste Dominique Ingres (French, 1780-1867). These painters were commanded enormous respect and influence in nineteenth-century Spanish art.

In 1853, Bonnat’s father died, prematurely ending his studies and requiring his family to return to Bayonne. There Bonnat quickly secured a 1,500-franc scholarship from the local Municipality to study at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Within a year, at at the age of 20 he had moved to Paris and entered the studio of Léon Cogniet (1794-1880).

By 1857 Bonnat had submitted three portraits to the annual Salon, all of which were accepted and initiated a life-long career of portraiture, which ensured a steady paycheck and a stream of important clients that included Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, the Empress Eugene, and the official images of four successive French presidents. Also in 1857, Bonnat competed for and won second place in the coveted Prix de Rome. Despite having lost state patronage to study in Rome, he was accepted to the French School in Rome and paid his own way. Studying there from 1858-1861, he produced three large-scale history paintings, Le Bon Samaritain (1859), Adam et Eve découvrant le corps d’Abel (1860) and Le martyre de Saint-André (1861), which were each sent to and accepted in the annual Paris Salon.

Almost immediately upon his return from Rome, Bonnat was welcomed into the French Academy and the upper echelon of respectable French art culture. In 1863 and 1864, two of his works are acquired by Princess Mathilde and Empress Eugénie, respectively. He was awarded the Légion d’Honneur (1867), made a member of the Salon jury (1869)--a position he would hold until his death--a member of the Institute de France (1881), a professor of at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris (1888), awarded the Grand Croix (1900), and made Director of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts (1905).

Despite having accrued significant and real recognition from the Academy, Bonnat courted controversy. As a young painter in 1863, he supported new reforms in the Ecole des Beaux-Arts that opened the very conservative school to, among other things, allow students to be instructed in oil painting. Beginning in 1869 as a member of the Salon Jury, Bonnat became a proponent for the controversial work of Eduoard Manet and Gustave Courbet. He was also a lifelong friend of Edgar Degas.

As I did research for this post, it occurred to me that, like Bonnat, many contemporary artists are struggling with the combination of the Classical Tradition and Realism in their work. The former emphasizes the ideal and the latter the real, often with particular emphasis on imperfection. I think that so-called "Classical Realists" would do well to look at the work of Bonnat, who combined a love of Ingres with a reverence for Ribera. They would benefit more looking at his paintings than from William-Adolphe Bouguereau (French, 1825-1905), for example, who was a strict Classicist.