[This post was inspired by a conversation I had with the talented and thoughtful painter Joseph Brickey. For more on his work, visit his website here.]

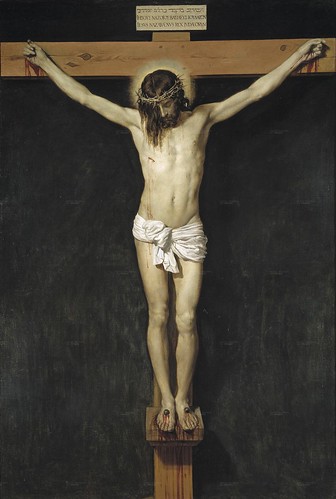

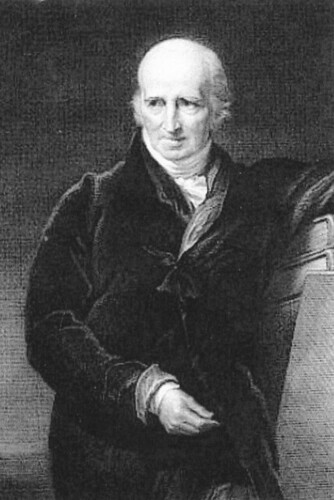

Over three quarters of what constitutes painting is comprised of drawing. If I had to put a sign above my door I would write: "School of drawing," and I'm sure that I would produce painters.

-Jean-Dominique Auguste Ingres (French, 1780-1867) (Henri Delborde. Ingres. sa vie, ses travaux, sa doctrine. Paris: Henri Plon, p. 123)

Previously on this blog, I have received comments questioning the sincerity, artistic integrity or creativity in nineteenth-century, academic painters and contemporary artists attempting to model them.The criticism is based on a belief that drawing accurately is not artistic (right-brain), but, in essence, an act of left-brained practice. In other words, a camera could do the same as the artist. I absolutely agree that an artist should not be a camera.

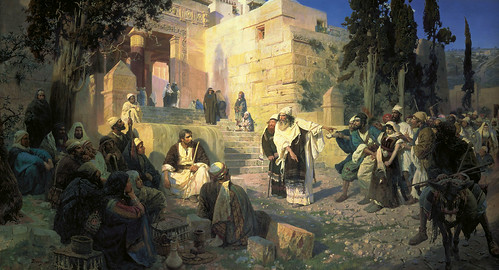

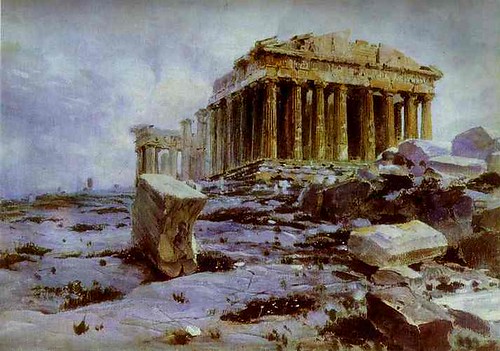

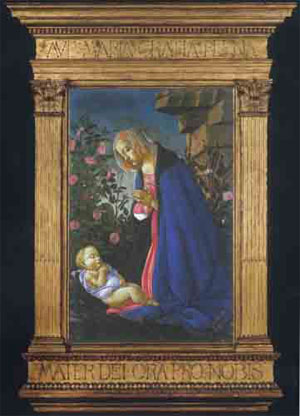

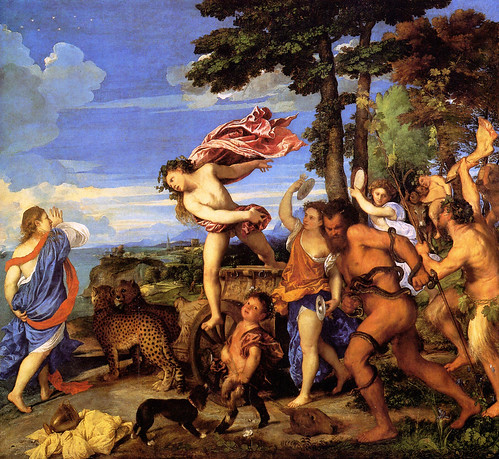

However, nineteenth-century, academic painting was not based on mimicking nature, but on observation combined with the ideal, sometimes described as the "antique."

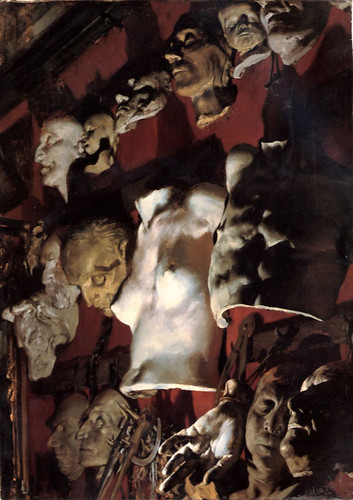

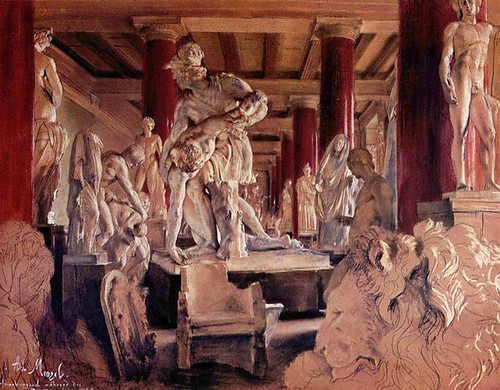

In France and much of Western Europe, the first half of the nineteenth century was dominated by an artistic philosophy that emphasized the dominance of line, or contour, over color. Drawing was considered the underlying structure of a painting and, therefore, was the principle skill taught in the major academies. In fact, it was not until the mid-nineteenth century that the Ecole des Beaux-Arts included oil painting as part of its curriculum. (Previous to that time, artists would learn oil painting in the ateliers of a master to whom they would be assigned in tandem with their studies or after graduation from the Ecole.)

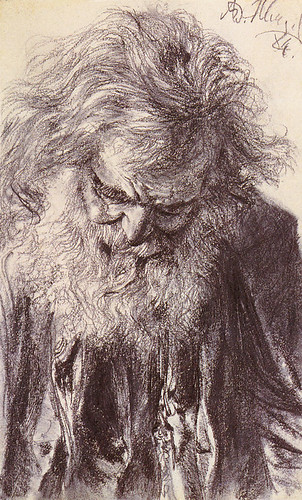

In his journal, Eugene Delacroix (French, 1798-1863) planned a study program and dictionary for artists writing:

The first and most important thing in painting is the contour. Even if all the rest were to be neglected, provided the contours were there, the painting would be strong and finished. I have more need than most to be on my guard about this matter; think constantly about it, and always begin that way. (Delacoix's Journal, April 17, 1824)

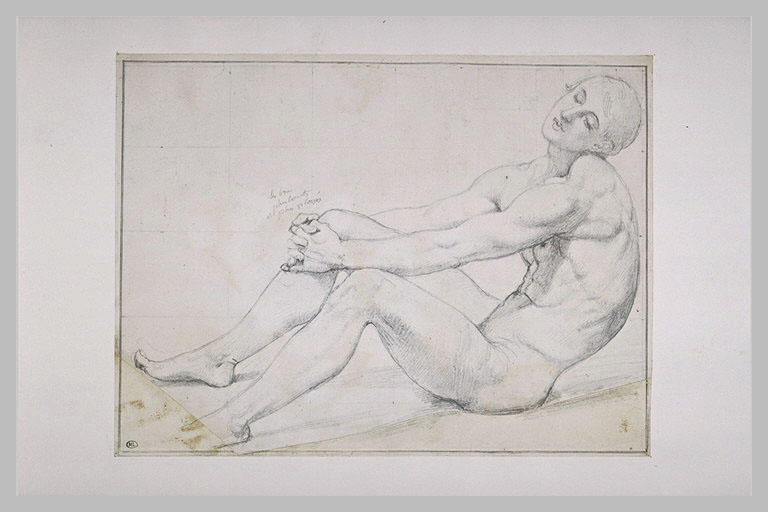

To modern eyes and to many artists who are attempting to resurrect the academic methods of the nineteenth century, the emphasis on drawing could be interpreted as an ability to correctly copy or mimic what the eye sees. This is an incorrect belief. Nineteenth-century academic drawing was only partially observational. In practice, it was a combination between observation of nature and classical construction based on an understanding of ideal form.

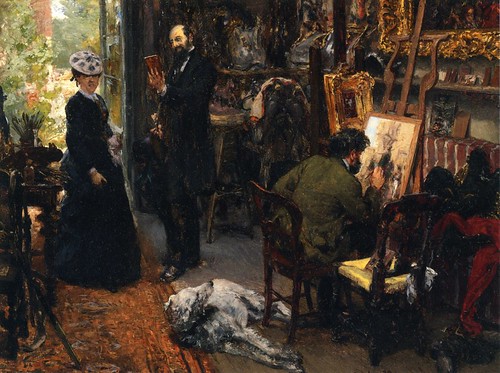

This combination of the ideal and the observation of nature was often objected to by the Impressionists. Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926) studied with the academic painter Charles Gleyre (Swiss, 1808-1874) and recalled an experience where the two perspectives on drawing clashed. Monet was working from a live, nude model and, on seeing his work, Gleyre reacted:

'It is not bad," he said, "but the breast is heavy, the shoulder too powerful and the foot too big."

"I can only draw what I see," I replied timidly.

"Praxiteles borrowed the best parts from a hundred imperfect models, to create a masterpiece," Gleyre replied dryly. "When you make something, you must think of the antique!"

That same evening, I took Sisley, Renoir and Bazille to one side: "Let's get out of here," I said, "This place is unhealthy, it is lacking in sincerity."

(Gustave Geoffroy. Claude Monet, sa vie, son temps, son oeuvres. Paris: Les éditions G. Cres et Cie, 1927, p. 26-27)

Again, academic painters were not interested in being cameras or making accurate copies of what they saw. Academic painting was deeply ideological and conceptual. It was based on the need to construct the human figure after the ideal. In this way, many artists today, including art historians, would be surprised to know that ideologically, academic painters had more in common with the avant garde Suprematism and Constructivism in the purity of geometry and line than the Impressionist did with those same movements.

An appreciation of nineteenth-century, academic painting--and, for that matter, many Old Masters--begins with an understanding of the ideology of the ideal and as the basis for painting.