Note: To protect privacy, the names used in this story have been changed.

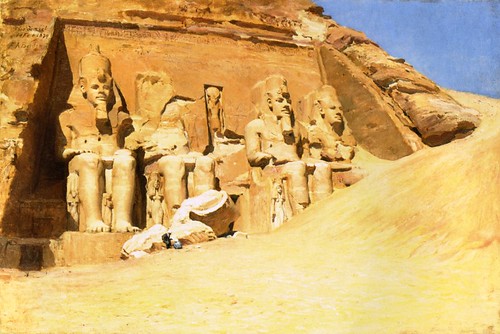

Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577-1640). Head of Medusa (c. 1617) Oil on canvas.

What started as a simple trip to Madrid to do research became a story worthy of Ian Flemming. Ferraris, international real-estate deals, London, Madrid, and world-renown Old Masters art dealers combined in a week-long painting adventure.

Recently, I flew to Spain on a research project. Getting off the plane at the Madrid, Bajaras airport, I was approached by a distinguished Englishman, John Jacobs. He was on his way to a business meeting near the Prado Museum and had overheard me talking to someone in Spanish--Jacobs didn't speak the language.

"Would I mind sharing a taxi?" he asked, "I could use the help and it would save us both money." My hotel was near the Prado. So, Jacobs and I got in the cab and got to know one another.

The ride was about thirty minutes. I learned that Jacobs was a consultant for a large British real-estate company working on a multi-billion-dollar deal that involved a group of Spanish investors. We didn't go into much detail about either of our careers. Stepping out the cab, he asked for my card, and I went on to my hotel without much thought about it; that is, until I got a call from Jacobs the next day.

"I met today with a very wealthy Spanish businessman. When I told him that I shared a taxi with an art historian, he wanted your number. Apparently, he has a Rubens painting and wants you to sell it," was Jacob's message.

A businessman from Madrid with a Rubens? I'm curious.

(As an art historian, I am approached regularly about paintings inherited from grandparents and found a yard sales. It is highly unlikely that any of these turn out to be masterworks or, even, a minor work of any worthwhile value. But, the possibility, no matter how minute, that someone in Arkansas has purchased a Titian from a Church charity sale makes every art dealer and historian want to at least take a look.)

On day three in Madrid, I get a call from Marcelo, the businessman with the Rubens. He asks to meet me at the Ritz Hotel in a few hours, where I could see an image and documentation of the Rubens painting. Rather than making me less suspicious, the idea of meeting at the Ritz seemed like an attempt to impress beyond a more disappointing reality. At least, that is what I thought before Marcelo stepped out of his Ferrari to shake my hand. (The likelihood that he rented a Ferrari in the few hours between the call and the Ritz, in an effort to impress me, was slim.) Having a Rubens now seemed credible.

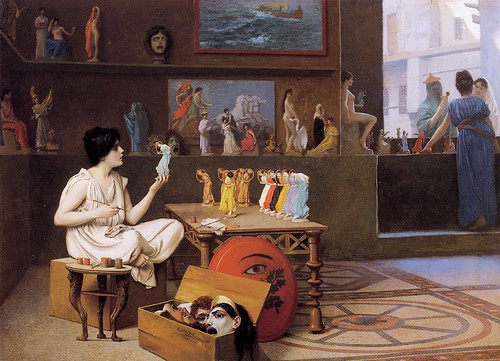

Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577-1640). The Holy Family with Saint Anne (c. 1628) Oil on canvas. (This is not the painting I was shown. For legal reasons, I am unable to show an image of the piece discussed in this post.)

He showed me the image of a Rubens modello (i.e. preparatory oil sketch) for an important altarpiece located in Northern Italy, along with a certificate of authentication from an art historian in Beverly Hills, California. "The painting is not actually mine," Marcelo explained, "I have a client that is doing a major real estate deal. He needs more cash and would like to sell the painting. He is not a painting expert, and neither am I."

In other words, there are several degrees of separation and supposed ignorance that made the situation seem simultaneously less credible and more credible. (Almost all Old Master paintings have a long history, but beware of complicated histories of ownership that include anyone that is cash poor, let alone a businessman from Texas.)

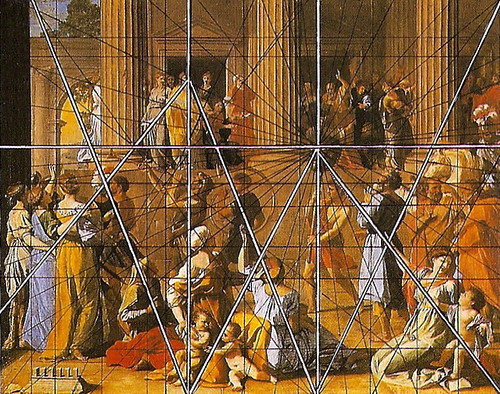

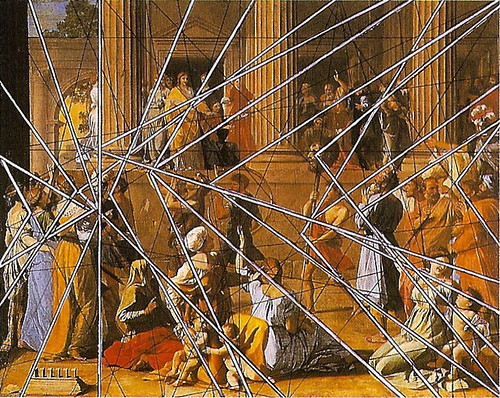

Peter Paul Rubens was one of the most prolific of the Old Master painters. Born in Antwerp, his formative training took place in Italy, where for several years he copied Renaissance painting and ancient statuary. Before returning to Antwerp, Rubens painted a number of altarpieces and other religious works. His working method included submitting a small sketch (modello, which literally means "model") of the intended painting to a patron for approval. Having received approval, he would use the modello as a map for the much larger, final work.

Marcelo's client wanted the modello sold in London to a dealer, but not an auction house--more alarm bells. And, Marcello planned to be in town to see Wimbeldon. "Could we meet with some dealers before or after one of the matches?" he asked.

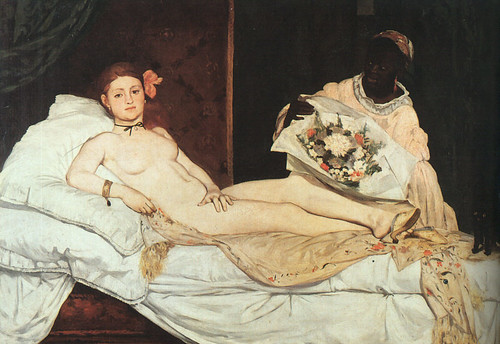

Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577-1640). Drunken Silenus (1618) Oil on canvas.

Arriving in London a few days before Marcelo, I took a photograph of the painting, along with certifying documents and met with two of the worlds foremost dealers in Old Masters paintings. (Though I will not mention their names, each has a gallery in St. James's Place in Westminster.)

These dealers are Olympians of the art world, with the ability to look at a painting and, within moments, place it in time and space together with its likelihood of authenticity. The first dealer looked at the photo for about 30 seconds, looked up at me and said: "Rubens didn't paint hands like that," and "the cherubs surrounding the Virgin look too thin to be by Rubens." His final judgments was it was authentically from the period, but more likely from a follower of Rubens.

The second dealer had sold a similar Rubens painting a few days earlier to the Getty Museum in California. He remarked on the hands of the modello too and said the overall composition "lacked a cohesive Rubens approach" with the figures being too separated in action from one another.

I called my Ferrari-driving friend from Spain telling him the news: It's not a paintings by Rubens. He brushed off the bad news and invited me to Wimbledon.

--

In sharing my experience with a long-time art dealer from the United States, he said that my story was familiar. Apparently, there has been a long practice of trying to sell supposed Old Master paintings to less-than-public buyers who are more likely to be ignorant of dubious works.

In my case, I was able to avoid being caught up in the a potentially huge mistake by taking the painting to two experts. It was a good lesson that, thank heavens, did not come with a price.

The best advice I got came from the second of the two dealers: "Don't trust certified documents from art historian in Beverly Hills."