(Dear Readers, I am currently on vacation and will be back and posting regularly at the end of September. Have a great summer!)

(Note: The following was written for the private collector who owns these two bronzes. I enjoyed my research so much, that I thought I would share it here, with his permission.)

At a time when Paris was the center of the art world Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904) was one of France’s most decorated artists. Principally remembered as a painter, his greatest contribution may well be his work as a sculptor. The works La Fuite en Egypte and Les Rameaux were both made in 1897, near the end of Gérôme’s career and at the height of his ability.

Born on France’s east coast, Gérôme received the reluctant permission of his father, an accomplished goldsmith, to study at the country’s most prestigious art academy, the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. There he excelled under the direction of Paul Delaroche (1797-1856) and Charles Gleyre (1806-1874). Gleyre’s studio, which placed emphasis on the revival of Greek forms in art, had a lasting affect on his student’s interest in classical subjects and models. Gérôme’s own work would span Classicism, Orientalism and Realism; traces of all three can be found in his later works.

When Gleyre was appointed Director of the French Academie in Rome in 1844, Gérôme followed. There he completed his academic education through close study of Old Master and Greco-Roman works. (Gérôme traveled throughout his career to Greece, Egypt and the Holy Land.) As a result of his studies, his works bore the technical virtuosity of an academic artist combined with personal first-hand knowledge of monuments, foreign landscapes and exotic peoples. La Fuite en Egypte and Les Rameaux directly reflect his study of bedouin costume and animals observed during a visit to the Holy Land.

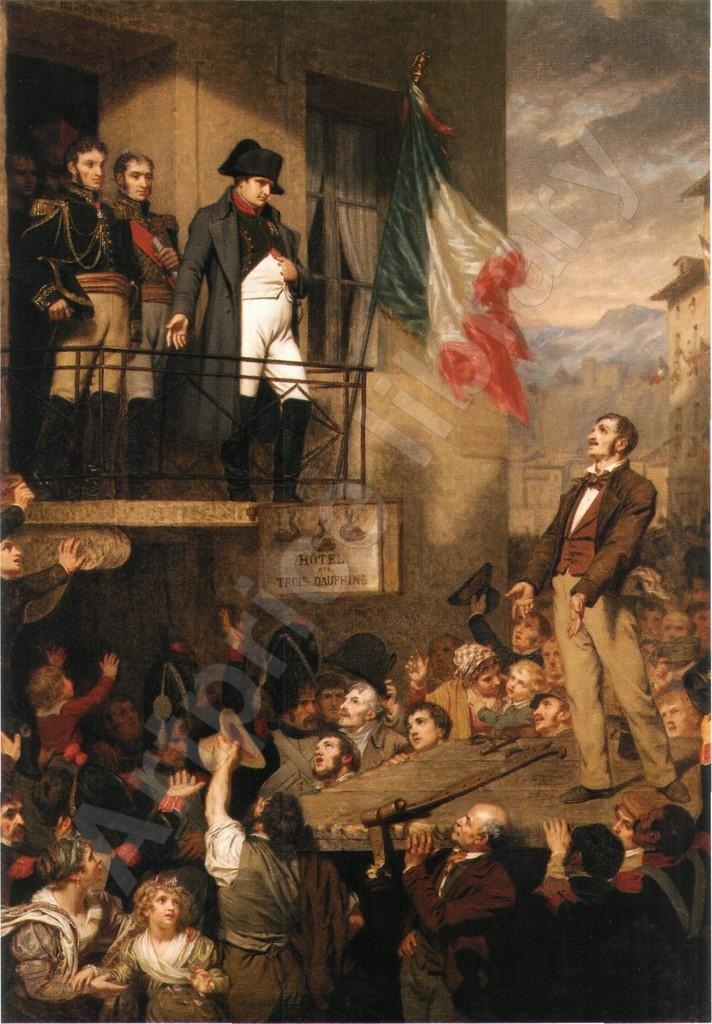

Returning to France in 1847, Gérôme enjoyed his first of many successes at the highly competitive Salon de la Société des Artistes Français. That year, the eminent French critic Theophile Gautier wrote: “Let us mark with white this lucky year, unto us a painter is born. He is called Gérôme. I tell you his name today, and tomorrow it will be celebrated.” Works by Gérôme were accepted nearly every year from 1847 to 1903. There they inspired popular novels and music. By the end of his life, Gérôme had been made a member of the Institute de France (1865), a knight in the Légion d’honneur (1867), and awarded the Order of the Red Eagle by King Wilhelm I of Prussia.

Such success merited prominent commissions from the state, as a well as a bevy of patrons, including the Empress Eugenie, who became a close friend. Today, his paintings and sculptures are found in many world’s finest museums including the Musée d’Orsay (Paris), National Gallery of Art (London), National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C.), Hermitage (St. Petersburg), Art Institute of Chicago, and Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York).

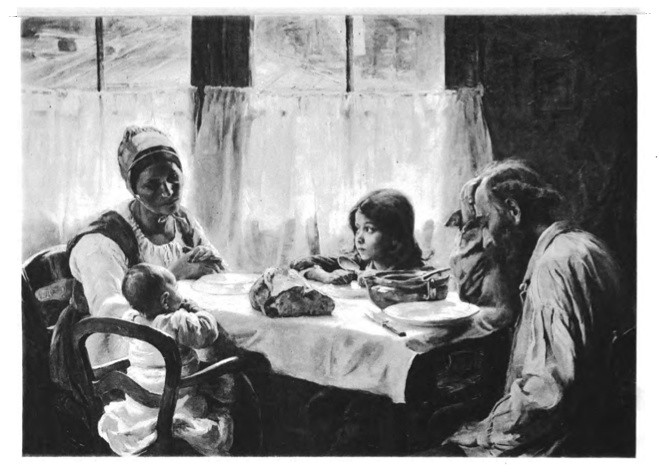

Géróme’s high profile had academic currency. He was hired as one of three studio teachers at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. There Gérôme fathered a dynasty of academic painters in France and America, among them Thomas Eakins (1844-1916), Frederick Arthur Bridgman (1847-1928), Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), Pascal Dagnan Bourveret (1852-1929), William M. Paxton (1869-1941) and Julian A. Weir (1852-1919). A lifelong tutor to many, he maintained a close relationship with his students beyond their studies.

In 1889, Gérôme travelled to Florence and Padua with two students: Edouard Detaille (1848-1912) and François Flameng (1856-1923) There he studied the equestrian works of Italian Renaissance masters, including Donatello and Verrocchio. The trip was a book end to the studies he began as a young artist and had first seen the works. He later wrote to a friend about the journey:

I went to Florence . . . I had stayed there as a youth and had not returned since. What a deception! What an eye-opener! I saw crumble--I won’t say all--but almost all my youthful heroes.

Rather than arrogance, here Gérôme displayed a genuine sense of disappointment and the honest assessment that then--in his late sixties--he may have moved beyond youthful lessons and on a level with the masters. It is possible this insight led Gérôme to look beyond standard models.

Late-nineteenth-century archeologists discovered color residues on Roman and Greek works, proving that the austere white marble we see today was, in fact, covered in bright blues, reds, greens and precious metals. Gérôme learned of the use of polychrome and incorporated them in his own works, including Les Rameaux and La Fuite en Egypte, which both bear the subtle but unmistakable use of polychrome unique to Gérôme.

The sculptures were produced during the last decade of his life, when Gérôme dramatically increased the amount of time and resources spent on his sculptures. In 1890, Gérôme hired Emile Décorchement to work as a full-time sculpting assistant. He also teamed up with the foundry of Siot-Decauville.

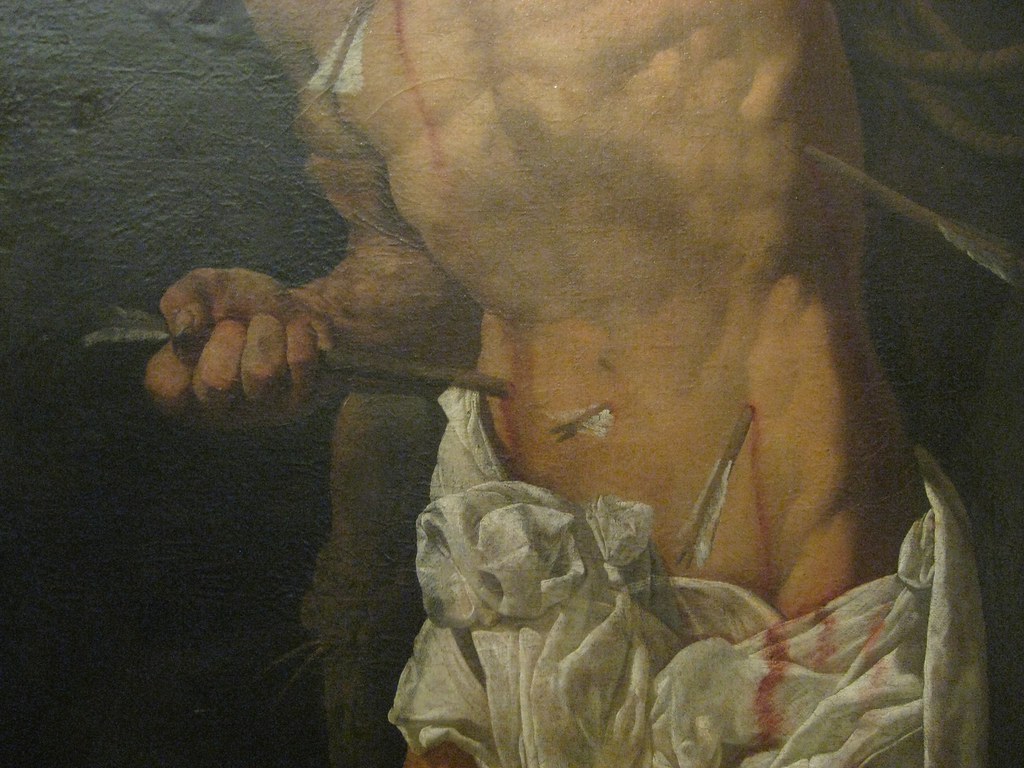

Established in the 1890’s, Siot-Decauville’s innovative ability to scale down large bronze models made their foundry especially attractive to Gérôme, who prided himself on fidelity to reality. The remarkable precision visible in Les Rameaux and La Fuite en Egypte were accomplished by Gérôme working with models twice the size of the finished bronzes. In this way, he was able to add details-the animals’ fur, the wilting leaves of Christ’s palm branch, and the gauzy folds of Mary’s bedouin clothing--with larger tools that would have been ineffective in smaller-scale versions.

In the late-nineteenth-century, table-top bronzes were an popular feature of tasteful interior decor. This pair of Les Rameaux and La Fuite en Egypte were cast in the same year as Gérôme’s painting, La Fuite en Egypte, was submitted to the Salon. According to his standard studio practice, Gérôme’s sculptures, sometimes in unfinished stages, were the inspiration for paintings and vice versa. In this case, it is unknown which work was first.

Les Rameaux captures the moment Christ enters Jerusalem (Matthew 21:1-11, Mark 11:7-10; Luke 19:28-44; John 12:12-19), on what is traditionally known as Palm Sunday, hence the branch in Christ’s left hand:

5 Tell ye the daughter of Sion, Behold, thy King cometh unto thee, meek, and sitting upon an ass, and a colt the foal of an ass.

6 And the disciples went, and did as Jesus commanded them,

7 And brought the ass, and the colt, and put on them their clothes, and they set him thereon.

8 And a very great multitude spread their garments in the way; others cut down branches from the trees, and strawed them in the way.

9 And the multitudes that went before, and that followed, cried, saying, Hosanna to the Son of David: Blessed is he that cometh in the name of the Lord; Hosanna in the highest.

10 And when he was come into Jerusalem, all the city was moved, saying, Who is this?

11 And the multitude said, This is Jesus the prophet of Nazareth of Galilee.

Palm Sunday marks the beginning of Holy Week, which ends with Christ’s resurrection on Easter Sunday. Gérôme indicates the journey ahead by placing Christ on a slight incline. As he enters the gate, Christ raises his hand in a sign of blessing, often attributed to Christianity, yet believed to be derived from a bircas kohanim (Jewish priestly blessing).

The juxtaposition of Les Rameaux with La Fuite en Egypte brings attention to details otherwise imperceptible. Christ sits on a femial donkey and Mary on a mael. Christ is on an incline, Mary on unvaried, steady ground.

La Fuite en Egypte depicts a pensive Mary, uprooted from her home and traveling to Egypt with family in tow. According to St. Matthew:

And when they were departed, behold, the angel of the Lord appeareth to Joseph in a dream, saying, Arise, and take the young child and his mother, and flee into Egypt, and be thou there until I bring thee word: for Herod will seek the young child to destroy him.

Despite the tumult inherent in the narratives, Gérôme shows Mary and Christ unfazed by their circumstances. These are not the contorted, pained figures of works often used for public ritual. They are works of private reflection.

When Gérôme created Les Rameaux and La Fuite en Egypte, he was 73. His last seven years were a flurry of activity. On the morning of January 10, 1904, Gérôme was found dead in his studio before a self-portrait of Rembrandt and his own painting Truth. He left a studio full of partially finished and un-cast plasters. Les Rameaux and La Fuite en Egypte were among his last finished works.

According to Ackerman there are at least three sizes of each statue known to have been cast. These were the first and largest versions and, therefore, their production, from start to finish, would have been overseen by Gérôme himself. In addition to their authenticity, Ackerman believed that they were created as a pair and not separate works. These two bronzes have been in the same family for three generations and are believed to have been purchased directly from Siot-Decauville. If true, these represent a rare combination. There is no similar pair known to exist in any public or private collection.

SOURCES

Gerald Ackerman. The Life and Work of Jean-Léon Gérôme with a Catalogue Raisonné (New York: Sotheby’s Publications, 1986

Gerald Ackerman, telephone interview with author, June 29, 2009

Mark Bradley. “The Importance of Colour on Ancient Marble Sculpture.” Oxford Art Journal. Vol. 32. (June, 2009)

Antonia Boström, ed. The Encyclopedia of Sculpture. Vol. 2 (London: Fitzroy Dearborn)

Lorinda Munson Bryant. French Pictures and their Painters. (New York: Mead and Company, 1922)

Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. Catalogue Illustré des Ouvrages de Peinture, Sculpture et Gravure. Paris: A. Lemercier et Cie, years 1847-1903

Helena Wright. Gérôme and Goupil: Art and Enterprise. (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1999)

H. Barbara Weinberg. The American Pupils of Jean-Leon Gérôme (Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum, 1984), 10-20)