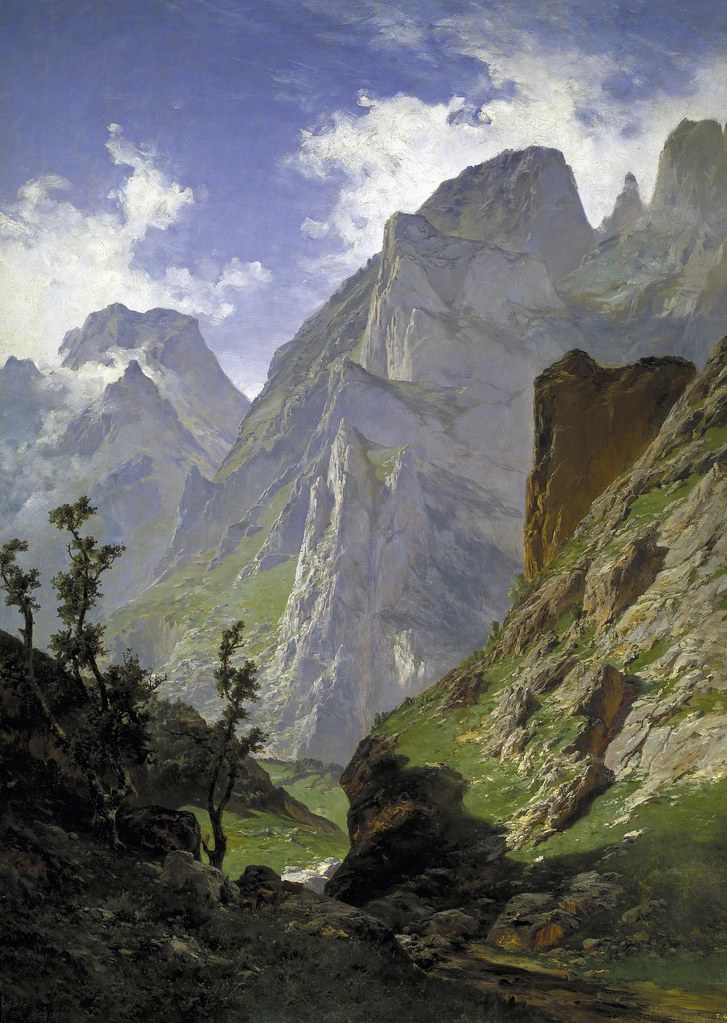

While not forgotten in Spain, Carlos de Haes' work has been little recognized elsewhere. As a teacher and award-winning artists, Haes is perhaps Spain's greatest landscape painter.

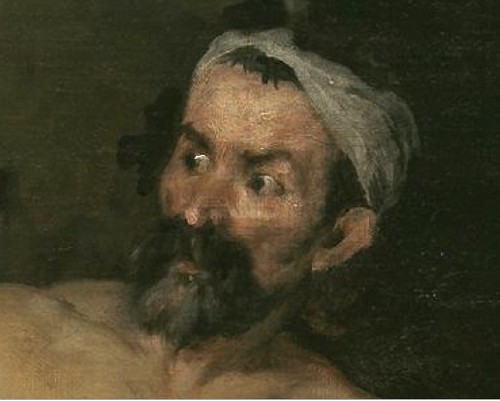

Carlos de Haes (Brussels, 1826-Madrid, 1898) was born in Belguim to Spanish parents. Due to financial troubles, the family was forced to return to Spain in 1835. There, Haes studied with Luis de la Cruz, a Court Painter to King Ferndinand VII and a member of the Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando.

In 1850, at the age of 24, Haes traveled back to Brussels to study Flemish landscapes. There he competed and regularly placed in Belgium's annual Salons. Six years later, Haes returned to Spain.

His international experience carried a great deal of currency in Spanish painting circles, and immediately set him apart from his peers who rarely studied beyond Spain and Italy. His dedication to landscape also changed the Spanish Academy's attitude towards landscape painting.

Despite having been accepted as a major genre in other European countries, during the first half of the nineteenth century, Spain had not widely participated in Romantic and Sublime landscape painting. Instead, landscapes were considered a second-rate genre, a necessary part of an artist's education insofar as it related to the composition of history painting.

Haes' work Cercanías del moasterio de Piedra (1858) was the first landscape painting to win a First Place medal at the Exposicion Nacional, Spain's equivalent of the Paris Salon. The award represented a giant leap forward in the estimation of landscape painting as a stand-alone discipline. Shortly afterwards, Haes was made a member of the Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, the nation's most prestigious art school. His appointment in 1860 to the Academia de San Fernandoand and subsequent teaching there effectively caught Spain up with other schools of landscape painting in Europe. As a teacher, Haes fathered a dynasty of Spanish landscape artists that continues today. Among Haes's more prominent students are Martín Rico y Ortega (1833-1908), Jaime Morera (1854-1927).

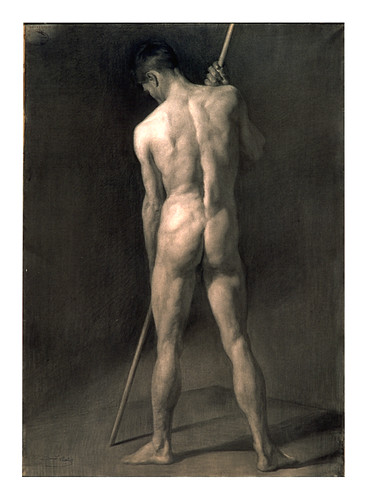

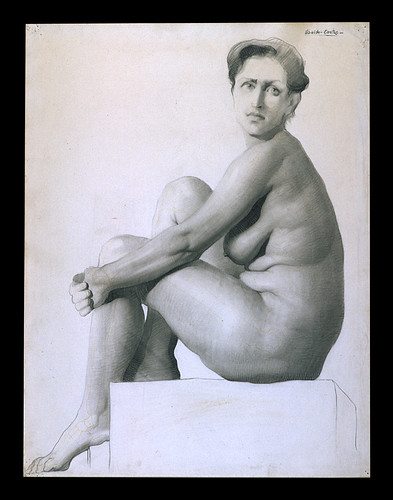

It could be argued that Haes' one of most important contributions to Spanish painting was with non-landscape painters. Through him, history painters, whose work enjoyed the widest attention at the Exposiciones Nacionales, developed a new appreciation and approach to landscapes, arguably bringing it on par with their figural work. Artists like Francisco Pradilla, José Casado del Alisal, Placenscia Maestro, were required to take Haes' course at the Academia de San Fernando considered a serious part of their large history paintings, sometimes producing numerous studies devoid of figures.

In particular, Haes brought to Spain an increased emphasis on three aspects of landscape painting: luminosity, porportion and direct observation from nature.

Traditionally, Spanish artists favored the use of sandy-colored grounds for use in painting. This created a unifying effect in their works, but resulted in the overall dampening of light. While Haes continued to use sand-colored and reddish grounds in his works, he would incorporate large patches of lead white and subdue the quantity of sandy grounds.

Very few of Haes' works exceed 150 by 200 centimeters. This was at a time when history paintings, often exceeding 6 by 10 meters, were competing for top prizes at Exposiciones Nacionales. Haes' landscapes, though bold in composition and epic in subject matter, maintained comparatively modest proportions. This set a precedent in landscape painting throughout Spain, which more or less continued throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, even when history paintings became more ambitious in size.

Finally and perhaps most importantly, Haes was a proponent of direct observation from nature and led several expeditions. This resulted to an almost nationalistic fervor for Spanish landscape painting, that featured Iberian natural wonders.

Today, Carlos de Haes' work can be found in nearly every major Spanish museum. However, the largest body and greatest works from his ouvre are held in the Prado Museum and not currently on display. A new wing of the Prado, dedicated to Spanish nineteenth-century art, is planned to open in 2012.

(Click here for a list of works and biography of Carlos de Haes by the Prado Museum.)

Bibliography:

- Carlos de Haes (1826-1898) en el Museo del Prado, cat. exp., Madrid, Museo del Prado, 2002.

- Cid Priego, Carlos, Aportaciones para una monografía del pintor Carlos de Haes, Lérida, Instituto de Estudios Ilerdenses, 1956.