I went to Madrid to continue research on Spanish painters, and left with an obsession for the Czech painter Alphonse Mucha (1860-1939).

Photograph of the CaixaForum building's vertical garden.

While walking to a cafe next to my hotel, I stumbled onto an exhibition on Mucha. Titled Alphonse Mucha: Seduction, Modernity, and Utopia, the exhibition is a joint effort between CaixaForum and the Mucha Foundation. It will be on show at CaixaForums new building, located across the street from the Prado, until August 31.

The CaixaForum is the cultural wing of the Caixa Bank. Banks in Spain are required by law to use a percentage of their profits for cultural purposes. As a result, many important exhibitions, like this one, have come to Spain in the past few years. As a rule they are free to the public, and are almost always accompanied by beautiful catalogs. Unfortunately, these catalogs, like the one accompanying the Mucha exhibition, are almost never available in stores or online.

Alphonse Mucha was born in Moravia (the modern-day Czech Republic). At the age of 25, he began studies at Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. Two years later, he would move to Paris and study at the prestigious Academie Julien in France.

Eventually, he would become friends with Gauguin and participate in Symbolist art shows with Bonnard, Grasset, Toulouse-Lautrec, Mallarmé and Verlaine. His participation in Symbolism, which has underlying metaphysical and religious beliefs, went hand in hand with his participation in Freemasonry.

Mucha was initiated in the Masonic Lodge of Paris in 1898 and continued to practice Freemasonry until he died, including references to it in many of his works.

One of my favorite moments in the exhibition came from a group of school children visiting at the same time I was. Their teacher asked them: "Does anyone know what a Masonic Lodge is?" The students seemed puzzled and no one was able to answer the question. Lesson: Don't expect a group of students in a country where 94% of the public is Catholic to know much about Masonry. Besides being an important Symbolist, Mucha was one of the most influential players in the development of Art Nouveau, for which he is most remembered.

His Work

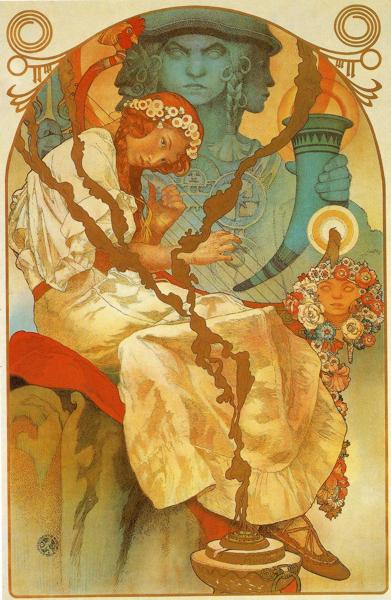

Alphonse Mucha. Madonna of the Lilies. (1905) Oil on canvas. Mucha Museum, Prague

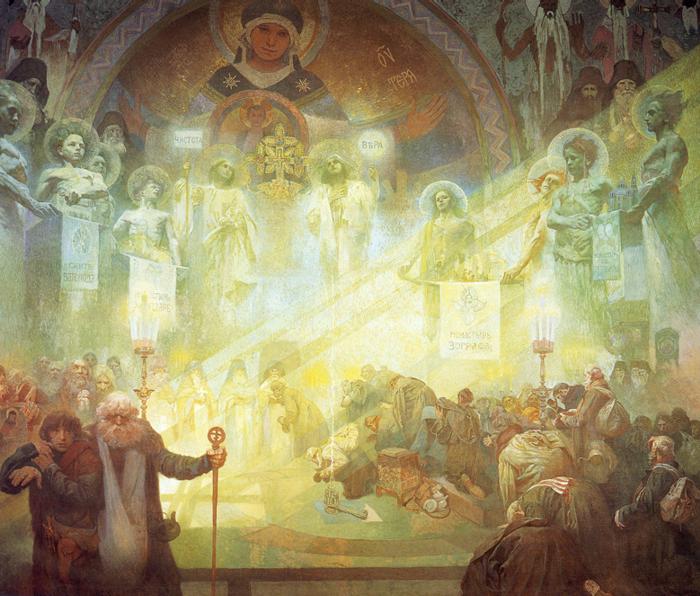

In contrast to the posters, the oils are full of light and use a generous palette. His ability to gradate from one color to another is extraordinary. While looking at The Apotheosis of the Slavs (1926), I thought of late-fifteenth-century paintings by Bellini, where he was just beginning to use oil rather than tempera, egg-based paints. Almost overnight, Bellini was able to make smooth shadows and gradual changes in color that were previously impossible. Mucha seems to crown nearly five hundred years of oil painting with a symphony of color that seamlessly glides from one bright color to another.

The Slav Epic

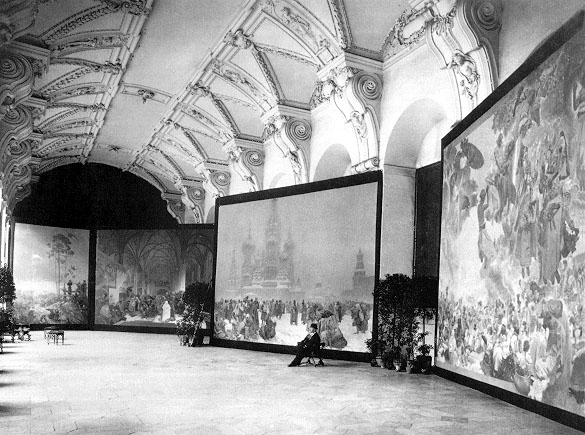

Photograph of Alphonse Mucha at the opening of the Exhibition of The Slav Epic. (1919) Klementinum, Prague.

Alphonse Mucha. The Abolition of Serfdom in Russia. (1914) Tempera on canvas. Mucha Museum, Prague

Alphonse Mucha. Holy Mount Athos. (1926) Tempera on canvas. Mucha Museum, Prague

(A hall along the courtyard. Pay attention to the pealing paint on the ceiling.)

(A hall along the courtyard. Pay attention to the pealing paint on the ceiling.)