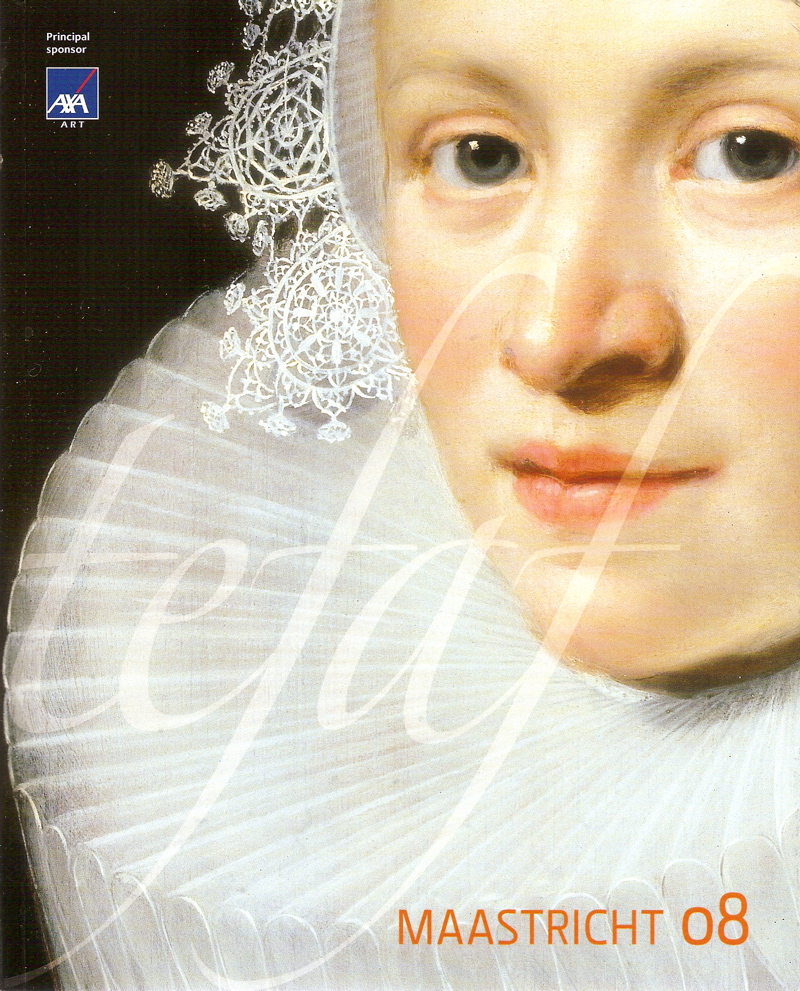

Cover from the guide to TEFAF

Friday, I took the train from London's St. Pancras International to Maastricht. It was the opening weekend of The European Fine Art Foundation (TEFAF) held in Maastricht in the Netherlands from March 7 to 16, 2008. Unlike museums with limited budgets, dealers at TEFAF have the cash and motivation to restore paintings. Nearly every painting had a new coat of shiny, barely-dried varnish. On one hand, paintings looked nearly new. On the other hand, some paintings had been through so many iterations of cleaning and varnishing that paint had become dangerously thin, obscuring brushwork and coloring. I often felt I was looking at them through an unfocused lens.

One of the many booths dedicated to Old Masters paintings

It was overwhelming to see so many Old Masters works under one roof. I was especially impressed by Richard L. Feigen & Co. (New York) and Whitfield Fine Art Ltd. (London). I could name a dozen others dealers in the Old Masters paintings wing. I wish I could say the same for nineteenth-century art.

There were myriad Monets and a plethora of Pissaros, but where were the academic painters?! I saw a Gerome, a L'Hermitte, and a Breton, but their colleagues from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts were poorly represented. Those that I saw were overpriced by 50 percent or more compared to my previous experience buying at auctions and from dealers in France and Belgium.

As a buyer who deals principally in nineteenth-century paintings, this was not the best venue. It might have been different if I were looking for Old Masters and Modern works.

Many of the dealers I know and have visited in London were there (e.g. Richard Green with his sons Mathew and Jonathan, The Fine Art Society, Whitford Fine Art.) They had saved their best work for the event. By the time I arrived on Saturday, the Exhibition had already been open for two days and several of the best paintings were already sold. (The early bird gets the worm . . . or Bruegel, Monet, Rembrant, van Huysum, etc.)

Also, TEFAF seems to be more for people who want to see and be seen than for those hunting for a deal. Those of us who have sold art before know that there are some people who buy something if they like it, regardless of price. This has both negative and positive consequences. Inflated prices make current stock more valuable, but they also lead to unrealistic expectations by buyers and sellers

I was surprised to learn from conversations with a few--to remain nameless--dealers that some 30 to 40 percent of their annual revenue comes from sales at Maastricht. So, either I'm missing something or there is a huge advantage to celebrity-level art events.

--

As a city, Maastricht is beautiful. It was too early in the year for tulips, but the town square, restaurants and entertainment overpowered any disappointment from the cold weather. A bit of advice: Book dinner reservations in advance, otherwise you will be eating at the bar.

Picture of the "old bridge" downtown Maastricht.

(A hall along the courtyard. Pay attention to the pealing paint on the ceiling.)

(A hall along the courtyard. Pay attention to the pealing paint on the ceiling.)