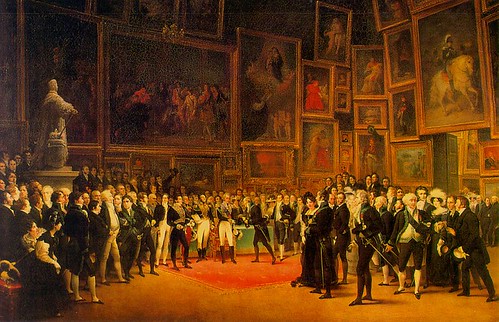

It's been over for a week, but I feel compelled to post pictures from my visit to the Grosvenor House Art & Antiques Fair. Before it ended, I was able to spend several hours with dealers and buyers one of the longest-running and grandest art fairs in Europe.

It's been over for a week, but I feel compelled to post pictures from my visit to the Grosvenor House Art & Antiques Fair. Before it ended, I was able to spend several hours with dealers and buyers one of the longest-running and grandest art fairs in Europe.

Despite the gloom and doom supposedly hovering over the art world, there was a great deal of optimism from both dealers and collectors at the Fair. I came on the next to last day, and nearly everyone of the dealers of nineteenth-century or traditional art I talked with had sold a large number of his or her inventory. This was not the case with contemporary art dealers I met. Though not scientific, to me it indicates the slow and steady, if not always sexy, appeal of working with established genres.

While there were world-class ceramics, furniture, modern art , works of silver and ancient relics, I was principally focused on nineteenth-century academic works. The photos from my visit, therefore, are a terribly unbalanced representation what was on view. Sorry.

Another thing to keep in mind: As in past review of fairs, I have taken photos of these images in person, at the fair and the results are sometimes surprisingly and sometimes less than ideal.

The first work that caught my eye was a remarkable sketch (above) by Géricault. Known for his obsession with horses--entire coffee-table books having been dedicated to them--its still startling to see one in person, and how much he can conjure with so few few lines.

Someone once told me a joke: "Question: What do you call the crumbs that fall from Richard Green's table? Answer: Cake."

The implication was that Richard Green Galleries is remarkably consistent in getting the best of the best. Most dealers and collectors would be satisfied to have the slightest portion of what this London dealer offers.

Previous to arriving several people had suggested that if I saw one work at Grosvenor, it should be the Green's Lesbia and her Sparrow (above). A cult following of British Olympic painters (e.g. Leighton, Tadema, Godward, and Poynter) has come fruition in the pas three decades. Poynter is one of the group's finest, and this is one of his gems.

Lesbia was the great love of the Roman poet Gaius Valerius Catullus (c.84-52 BC) and the subject of 25 of his surviving poems. Poynter chose one in particular as the subject for this painting:

Sparrow, my girl’s darling

Whom she plays with, whom she cuddles,

Whom she likes to tempt with finger-

Tip and teases to nip harder

When my own bright-eyed desire

Fancies some endearing fun

And a small solace for her pain,

I suppose, so heavy passion then rests:

Would I could play with you as she does

And lighten the spirit’s gloomy cares!

(cited in My Mistress’s Sparrow is Dead, ed. Jeffery Eugenides, Harper Perennial, London, 2009, p. x).

Poynter began his career working in stained glass and cabinetry. This probably contributed to his heightened use of color and remarkable ability to imitate various materials, a skilled often needed wood graining.

Sir Alfred Munnings described Frederick Henry Prince (above) as "one of the most amazing characters I had ever met . . . a grown up boy." This painting was commissioned by Prince, showing him at one of his favorite activities and the kind of scene Munnings had made his name producing: sporting pictures. If you are not familiar with Munnings' work, you can be forgiven. Due to the way his paintings are sold--at sporting auctions and not nineteenth-century art auctions--outside of Great Britain, Munnings has not received the recognition his skill merits.

Everything in this painting is world class: the figures, the composition, observation of nature, and the economy of materials (note in particular the tails of the dogs; some only consisting of a single stroke.). Munnings is a genius.

Leytens is one of those great Flemish painters following in the wake of the Brueghel dynasty. There were so many wrote compositions mass-produced in enromous artist studios. Works that are able to transcend the typical formulae to create something original and compelling. The light and darks Winter landscape . . . (Above, and pitifully captured by my camera) made this work visible from far away. Upon close inspection it has all the charm of cabinet paintings from the period that were often meant to be viewed with a magnifying glass.

Behold the power of narrative painting. A family has lost the recently-deceased patriarch's will, and a scoundrel--seen exiting stage right--trying to take advantage of the resulting ambiguity. After searching through numerous documents--in the foreground and on the table--the will is held high and the rightful, and obviously deserving, inheritors are vindicated. Mustached evil is chased out the door by the family dog, the embodiment of fidelity.

Though I haven't found it yet, it is highly likely that George Smith produced The Will Found to be a print. Prints and contracts with printers were often more lucrative for painters than the sale of the original work. Such was the case with Holbien in the eighteenth century.

There is disappointingly little written about James Webb, who regularly exhibited at the Royal Academy. The preponderance of his output was in watercolor, not oils. Yet, he shows an astounding facility and painterliness in this work.

Look at this beautiful passage of clouds!

Robert Bowman is one of the world's great dealers and experts of nineteenth-century sculpture. For several years he maintained both contemporary and nineteenth-century galleries. However, a few years ago, he downsized by closing his nineteenth-century gallery and showing those works almost exclusively at fairs like Maastricht and Grosvenor.

This year Bowman had several works by artists like Leighton and Rodin that can be seen in larger scale versions in museums around the world. Seeing The Sluggard (above), at this small size gave me a completely different eperience than the larger-than-life version I am used to seeing at the Royal Academy in London. While I find the larger version imposing and dynamic, this appears more delicate bring out a kind of beauty I hadn't seen in the other. Also, the patina of this smaller work is beautifully rendered.

Claudel's piece L'Abandon (above) was given a place of prestige at Bowman's booth; and, it deserves all the attention it gets. According to Bowman:

This 1905 rare bronze . . . is the earliest edition ever seen on the open market. This is the second of an edition limited to 18, the first cast having been kept by the owners of the foundry.

Claudel, was 18 years old when she met and began a 15-year affair with August Rodin, aged 42. Understandably, Rodin had an enormous influence on her work. Bowman relates that the statue borrows from and reverses the gender roles of Eternal Spring (1881) by Rodin and is based " on the eponymous 5th century Hindu legend in which the heroine, Sakoutala, loses the affection of her beloved prince only to regain it once more."

Baily is the sculptor of the iconic statue of Lord Nelson, standing atop the column in Trafalgar Square in London, perhaps the most seen statue in the country. The monument to Nelson was completed in 1843, and Psyche (above) statue was finished the same decade.

Psyche, unlike the statue of Lord Nelson, is meant to be seen at an intimate range. The delicate butterfly is held in beautifully articulated fingers that include minute details of fingernails and lines in the palm.

The statue is the epitome of idealistic beauty and looking at it, even briefly, can drop your blood pressure by several points.

Directly across from the Bowman Galleries stall was the that of Joanna Booth, a dealer in mediaeval and archaic works of art. St. Martin dividing his cloak for a beggar (above) is a remarkably fully-realized piece. This single angle of the work does not adequately capture the full effect it has in person. The beggar with a wooden leg, the bold gesture of the Saint cutting the cloth, and the interesting choice to make one so much larger than the other, the author's mastery in depicting varied textures. . . here it looks almost like a cartoon caricature; but, in person, it takes on a majestic air that is humbling.

For me, going to museums is exhausting, but I rarely get weighed down at fairs like Grosvenor. This is due in part to the kind of paintings, like The Toyshop Window (above) rarely, if ever, shown at museums. Museum are after a kind of gravitas in their paintings. Unfortunately, this makes a whole category of paintings, full of charm and humor, absent from public exhibitions. Like eating heavy foods all the time, I get museum indigestion. Sometimes, I want dessert or, at least, a sorbet, to cleanse my palate.

I wanted to begin and end this post with my favorite work from the exhibition: For the Squire (above) by John Everett Millais. Millais's works rarely appear in the private market; and, when they do, it is not often in the form of a fully-realized canvas. It is the kind of work that will never be featured in a show due to the lack of drama. It has all the so-called sentimentality that turns many off to the period.

For me there is a purity of spirit, an innocence in this work that is communicated in a way that only painting can. The narrative--the delivering of a letter--is the lightest of pretexts for painting this little girl. Unlike the style that characterized his early Pre-Raphaelite works, this painting is not consumed with details. (The background, fabric, and hair are more suggested than copied.) Done when he was 53, it seems the product of a mellowed Millais.

--

There are many, many more works not included in this post that I have uploaded to my Flickr account. (In some cases, a work is followed by a photo of its label. That's my way of remembering what I've seen and where I've seen it.)